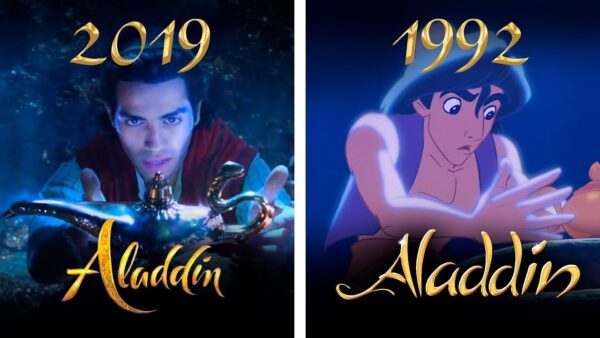

In May 2019, Disney released a live-action version of Aladdin, which tells the story of an affable street-urchin who accepts the services of a trickster genie to win over the sultan’s daughter, Jasmine. The film is an adaptation of a folktale from the 18th-century, Arabic-language collection, A Thousand and One Nights. Twenty-seven years ago, Disney’s animated version of Aladdin was the highest-grossing film of 1992, earning over $346 million in worldwide box office revenue.

While the 1992 movie had all the fairy-tale elements to attract viewers — adventure and intrigue, an evil villain, a plucky underdog, a forlorn princess trapped by tradition, and an array of supporting characters, Aladdin didn’t fare well with critics. Some were alarmed by the film’s stereotypes and generalizations about Arabs and the Middle East. Iconic film critic, Roger Ebert, wrote in his 1992 review: One distraction during the film was its odd use of ethnic stereotypes. Most of the Arab characters have exaggerated facial characteristics – hooked noses, glowering brows, thick lips – but Aladdin and the princess look like white American teenagers. Wouldn’t it be reasonable that if all the characters in this movie come from the same genetic stock, they should resemble one another?

After the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee complained about song lyrics describing the setting in the film, “Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face,” alternate lyrics were dubbed into the video and soundtrack releases. But, a completely white cast voiced the film, and the association of Arabs with violence, greed and other negative traits suggested that Hollywood was insensitive at best and xenophobic at worst. The film remains controversial to this day.

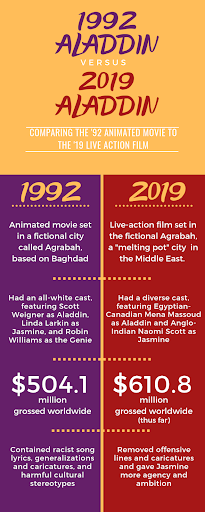

Thus, when Disney reported in 2016 that a live-action adaptation was in the works, director Guy Ritchie had to contend with the original film’s controversial legacy. Could he overcome the perception that the story was inherently bigoted? Was it possible to accurately depict cultural nuances using a fairy tale? Reviews have been mixed but the film has been popular, nonetheless: the 2019 film surpassed the original film within a month of its release at the box office. Aladdin earned $604.9 million worldwide after a little over two weeks in release, with $232.4 million domestic and $372.5 million international for the musical remake. As mentioned above, the original, one of many films released as part of the Disney Renaissance, made $504 million worldwide over its entire box office lifetime.

Here, TeachMideast provides you with in-depth background and context so you can decide for yourself whether society is succeeding in its demand that Hollywood do a better job portraying minorities. We take a look at the origins of the folktale, the previous dramatic portrayals of the story, the 1992 animated film, and how the filmmakers tried to overcome past controversy in the latest rendition of Aladdin. At the end of the overview, you can also find resources section for further exploration in the classroom.

Here Are 5 Points to Keep in Mind

1. The original Aladdin was actually Chinese

While the true origins of the tale of Aladdin cannot be completely verified, the story is often attributed to French writer Antoine Galland, who claimed a Syrian told him about a boy and a genie in China. A Syrian named Hanna Diyab did apparently meet with Galland at some point, but it remains unclear how much, if any, of the story came from him. Versions of Aladdin from the 19th and well into the 20th centuries depict the main character as culturally Asian, not Arab.

Throughout the Victorian era, “Aladdin sport[ed] a Manchurian queue and Chinese slippers, and the architecture feature[ed] distinctly Chinese pagodas.” The emphasis on the Chinese aspects of Aladdin during this time period through the use of “chinoiserie” (the imitation of Chinese motifs and techniques in Western art) was especially popular. In the examples below, the illustration of Aladdin on the left, circa 1930 by an unknown artist, (Credit: Getty Images/Hulton Archive), and the illustration on the right from the early 20th century (Credit: Alamy), both clearly depict Asian clothing and settings.

Hollywood’s Interpretation of the Fairy Tale

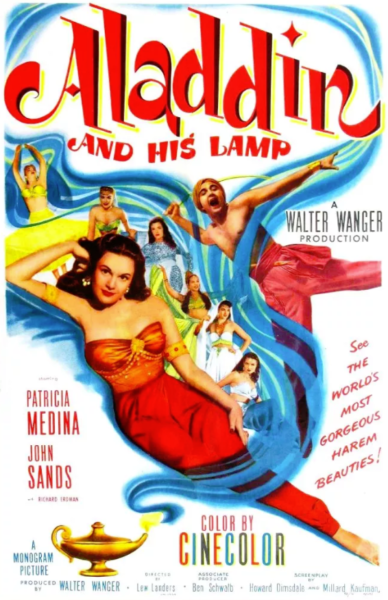

With the advent of the Hollywood film industry, the story returned to its fabled Middle Eastern origins, replete with exotic and exaggerated stereotypes — note the poster for a 1952 version of the story below! The 1992 Disney animated film placed the story in the Middle East but the change in scenery was not necessarily based on historic or contemporary accuracy. Rather, “the story was often presented as a hybrid tale of the exoticized Orient meeting modern English-language styles and fashions,” according to one critic. Authenticity was not a major consideration.

A Hybrid Cultural Setting That Is Influenced by Global Events

2. While the movie is set in a city based on Baghdad, Iraq, Aladdin contains aspects of multiple Middle Eastern and Asian cultures

Most people consider Aladdin to be set somewhere in the Middle East. Ron Clements and John Musker, the directors of the 1992 film, said in 2015 that the movie was originally intended to be set in Baghdad, Iraq. However, the outbreak of the first Gulf War (a conflict involving Iraq’s invasion of neighboring Kuwait) in the early 1990s prompted the directors to set the story in the fictional city of Agrabah, an adaptation of Baghdad. The names Jasmine and Aladdin are both of Middle-Eastern origin, with “Aladdin” being derived from Arabic while “Jasmine” has its roots in Persian.

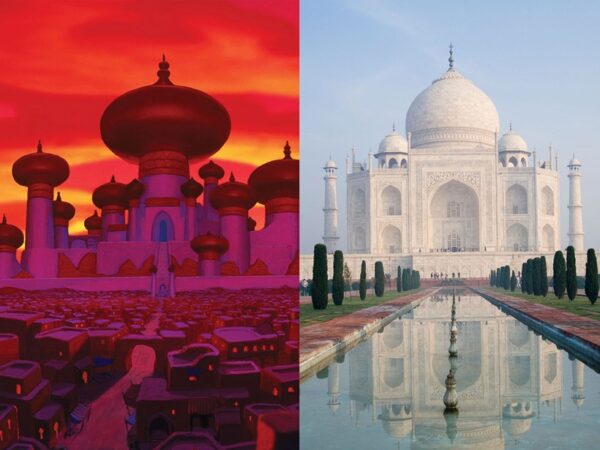

Aspects of the story also have Indian influences, including Jasmine’s Indian tiger Rajah, and the sultan’s palace in the animated film looking remarkably similar to the Taj Mahal.

In the 2019 film, Agrabah is “a port city that rests on the cusp of Eastern and Western nations, making it a thriving trade town and bringing together a melting pot of cultures and influences.” The production designer used Turkish, Persian, and Islamic influences for the set design. Background characters wear clothing from a wide array of cultures, including Afghan payraans, Indian saris, Omani daggers, and turbans from multiple cultures.

An Attempt to Correct Past Mistakes

3. The live-action 2019 film is more culturally and socially sensitive than the 1992 animated film

While the voice cast of the 1992 movie was entirely white, the live-action film boasts a diverse cast. Mena Massoud, who plays Aladdin, was born in Cairo, Naomi Scott (Jasmine) is of Anglo-Indian descent, Numan Acar (Hakim) is Turkish, and Nasim Pedrad (Dalia) and Navid Negahban (The Sultan) are Iranian. Creating a diverse and primarily non-white cast for the film was a huge step in accurately portraying a land set in the Middle East and moving towards greater diversity in Hollywood.

The 2019 film also removed several instance of the most egregious racism from the animated film. The song Arabian Nights, which initially referred to Agrabah as a place where “they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face/it’s barbaric, but hey, its home,” has altered lyrics. In updating the film and its content, Disney sought advice from the Muslim Public Affairs Council, an LA advocacy group, as well as groups “comprised of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and Muslim scholars, activists, and creatives.” Due to the advisory group’s input, the film avoided the crude portrayals found in the 1992 movie. Furthermore, these advisors helped ensure that any Arabic-language text was correctly displayed and that the setting and dress were more culturally realistic.

Jasmine was also given a more complex plot line in the new adaptation. Instead of simply being upset with her father for restricting who she can marry — as in the 1992 version — Jasmine aspires to be the first female sultan and is frustrated by her father’s refusal to consider her because of her gender. The new-and-improved, feminist Jasmine even performs an original song, Speechless, in which she sings about not allowing men to silence her.

Did the Filmmakers Do Enough?

4. The new movie had its fair share of negative press during production

The casting of Naomi Scott, who is of English and Indian descent, upset some fans and critics who believed the role should have been played by a Middle Eastern actress. Some accused Disney of reinforcing “notions of “Oriental interchangeability,” pointing to the fact that name Jasmine has Persian roots, not Indian. Others defended Scott, noting that the story includes Indian aspects, Agrabah is meant to be a melting pot of cultures, and Jasmine’s mother is said to be from “another land,” making it entirely plausible that Jasmine could be an Indian woman.

Disney also came under fire for allegedly darkening the skin of white actors and crew members. Disney claimed they included white extras “only in a handful of instances when it was a matter of specialty skills, safety and control,” but many still criticized the company for not taking the opportunity to hire more actors and crew members of Middle Eastern and South Asian heritage.

Outrage flared again when Disney announced that they had cast white actor Billy Magnussen in a newly-created role of a Scandinavian prince vying for Jasmine’s attention. Fans questioned the need to include this new character — whose appearance was ultimately inconsequential — and wondered why a white character had to be added to a refreshingly-multicultural film.

What’s the Final Verdict?

5. Some viewers have dismissed the 2019 Aladdin as racist and Orientalist, while others maintain the new adaptation is an improvement on the original film

Take a look at both sides of the argument:

The Critics

- Critics of the film and the story itself argue that the tale of Aladdin is inherently racist and Orientalist, and, regardless of the setting, is simply a colonial European view of the “exotic” East. The New York Times critic Aisha Harris argues that Disney should stop trying to improve stories that are problematic and should leave them in the past, instead focusing on new stories that won’t be tainted by previously offensive versions.

- The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), a Muslim advocacy group, released a statement in May 2019 saying that, “The Aladdin myth is rooted by racism, Orientalism and Islamophobia…The overall setting, tone and character development in the ‘Aladdin’ story continues to promote stereotypes, resulting in a perpetuation of Islamophobic ideas and images.”

- While Agrabah is apparently described as this “melting pot” of ethnicities, that concept comes from the deeply-problematic 1992 animated film. Critics say the movie producers have used this “melting pot” description as an excuse to be lazier in casting. Evelyn Alsultany, an expert on the representation of Arabs and Muslims in U.S. media, says that “Arabs, Persians and South Asians are not the same, and casting them as such reinforces Orientalist notions of interchangeability. By erasing distinctions between MENA cultures and people, it feels like the filmmakers are saying that brown is brown, and we’re all basically the same to them.”

- In writer Steve Rose’s words, “fantasy locations cannot conform to reality, but they often conform to their creators’ prejudices.” While Agrabah is fictional, many argue that that is not an excuse. Middle Eastern critic Maha Albadrawi says that, “I understand that Agrabah is a fictional amalgamation but we now live in a time in which it is possible to build believable fictional worlds inhabited by people of colour — think Wakanda from Black Panther and Motunui from Moana.” Especially since people of Middle Eastern descent have been so mocked and vilified in American media, many see Aladdin as more than just a movie for entertainment.

The Defenders

- Others say that accusations of racism are overwrought. Supporters of the movie point to the fact that Agrabah, despite being supposedly based on an actual city, is fictitious. Given that is fictional, who’s to say it can’t include many different races and ethnic backgrounds? Fantasy worlds are not meant to perfectly align with real-life racial boundaries. Even real-life cities are melting pots of different languages, racial and ethnic groups, and religions, just as Agrabah is. The movie itself never explicitly states where in the real world the story is taking place, so all fans can do is speculate.

- Proponents of the film also encourage focusing on the great strides the 2019 film made in being more diverse and inclusive. By casting actors of different nationalities and ethnic groups, the movie was able to showcase a wide range of cultures, giving a platform to voices traditionally omitted in Hollywood. It can also be argued that outrage about Naomi Scott is invalid, given the visible Indian influences in the story.

- It is also important to think about all the improvements the 2019 movie made over the 1992 adaptation (see #3 on this list above!). While the 1992 film is widely perceived as problematic, many point to the fact that the worst parts (including racist lyrics and caricatures) have been removed and replaced with accurate Arabic script and culturally-appropriate dress.

Resources

Watch the trailer for Aladdin, or see the movie in theaters now, and make your own conclusions. You can also see our lesson plan on exploring stereotypes with American film and television, which offers guided activities for your students.

Questions for reflection in the classroom:

- How do you feel about Aladdin? Did watching it ever make you uncomfortable?

- How is your family’s culture represented in film, television or literature?

- Why is it important to have culturally-accurate depictions in film and television?

- Who should tell stories of other places?

- Is it okay to watch a movie if it includes offensive parts? Why or why not?

- Why is there so little Middle Eastern, Arab or Muslim (or other minority group) representation in film and television?

- How do you see this issue changing in the future?

- What can you do to be more aware of cultural insensitivity and misrepresentation in pop culture?

Further exploration

The Middle East has a robust entertainment industry and creative voices in the region regularly share their stories through film, television, music and other media forms. There are now more opportunities for people in the United States, and elsewhere, to access regionally-produced entertainment from the Middle East. New foreign series, such as Jinn, available now on Netflix, may also rely on fantasy or folk culture, but they provide authentic place settings and use local talent and perspectives. Jinn’s Lebanese director Mir-Jean Bou Chaaya has said, “this is a great opportunity to portray Arab youth in a very unique way. The level of authenticity Netflix is trying to achieve with this show is definitely what attracted me the most to be part of this project.”

Think about the following questions:

- Who do you think the audience/consumer is for this and other emerging Arabic-language series?

- Why or why wouldn’t American teens be interested in this type of programming?

- Why are streaming services developing regional content?

TeachMideast Aladdin Infographic

See some of the major differences between the films in this chart designed by our summer interns.