Murtaza Hussain, The Intercept

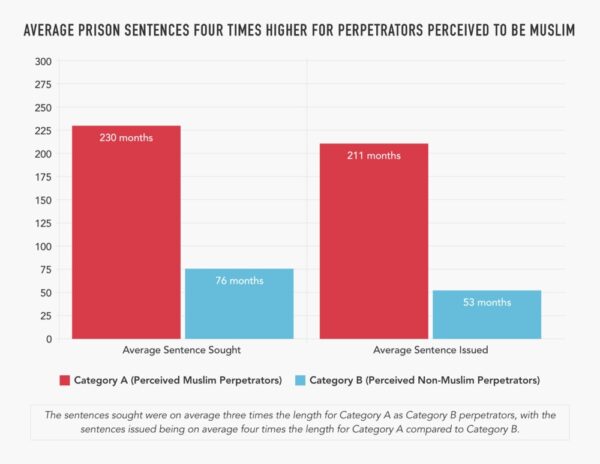

AMERICAN COURTS TREAT Muslims differently, a study by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding says. Among perpetrators of ideologically-motivated violent plots, those who were perceived to be Muslim received sentences that were four times longer than non-Muslims involved in similar cases. The disproportionality carried over into the court of public opinion, too: cases of attempted violence by Muslims received 7 1/2 times more coverage from major media outlets, while successful plots were also covered twice as much as those of non-Muslims. [Ed. note: Separate research done by the University of Alabama in July 2018 found that terrorist attacks committed by Muslim extremists received 357% more US press coverage than those committed by non-Muslims; researchers controlled for factors like target type, number of fatalities, and whether or not the perpetrators were arrested before reaching their final statistic.]

These findings are contained in a new report, titled “Equal Treatment? Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States,” released by the Washington-based Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU). Built on years of research on cases of planned or successfully-executed acts of ideological violence in the U.S., the report highlights significant discrepancies in the way the judicial system and media treat such acts, depending on the background of the suspected perpetrator.

“The findings of this report build and expand on existing research, and provides quantitative backing to many people’s instinctual perceptions of what has been going on in the media and in our legal system,” said Kumar Rao, a fellow at ISPU and one of the co-authors of the report. “As it relates to acts of ideological violence, there is, frankly, a double standard in how perpetrators are described in the media, as well as how they are treated in the courts.”

Graphic: ISPU

The report draws on public databases that compile information on acts of ideological violence attempted or carried out in the United States between 2002 and 2015, including The Intercept’s Trial and Terror database, which tracks prosecutions of cases involving international terrorism. Among these cases were numerous bomb plots, plots to attack government buildings, attempts to stockpile assault rifles for the purpose of carrying out attacks against civilians, and completed attacks that led to two or more fatalities. (The researchers did a media analysis of completed attacks, but could not do a legal analysis, as those incidents often led to the death of the perpetrator.)

The U.S. government has prosecuted 891 people for terrorism since the 9/11 attacks. Most of those people never get close to committing an act of violence but are charged with material support for terrorism, criminal conspiracy, immigration violations, or making false statements. These non-violent and frequently-vague offenses nonetheless give prosecutors leverage to obtain easy convictions or plea bargains.

The researchers used seven different variables to control for the severity of the crime in cases comparing perceived Muslim and non-Muslim perpetrators, including whether the plots resulted in fatalities, utilized deadly weapons, or involved co-perpetrators. For purposes of analysis, the report refers to individuals “perceived” to be Muslim by the description of their motives in law enforcement statements and the media. When comparing highly-similar cases in terms of intended harm, the researchers found profound disparities in the way cases were treated in the courts. In cases involving Muslim defendants, the study found that prosecutors sought three times longer sentences than they did in comparable cases involving non-Muslim defendants, seeking an average of 230 months in prison, compared to 76 months. Upon conviction, the sentences that Muslim defendants received were, on average, 211 months long, four times longer than the average 53-month sentences of non-Muslim defendants.

“What was really interesting is that in the majority of cases involving people perceived to be Muslim, the perpetrators were not acquiring weapons on their own, but were instead being provided with them by government agents — yet they were being charged more heavily. Meanwhile, in cases involving non-Muslim perpetrators, you very often had people actually making explosives and stockpiling firearms. They didn’t need the FBI to go over and hand them weapons, because they already had them.”

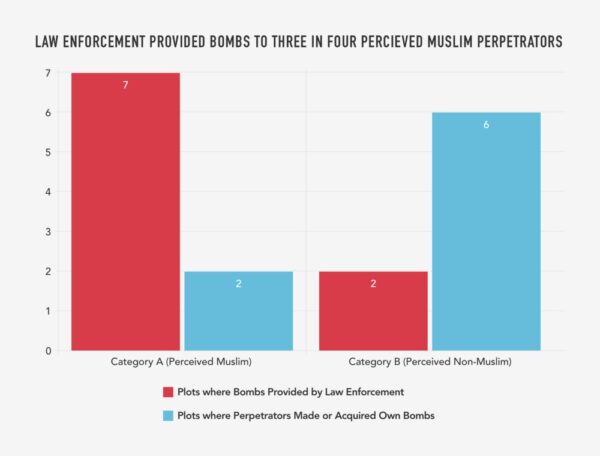

Law enforcement also used very different tactics in cases involving Muslim and non-Muslim perpetrators. In 66% of convicted plots involving Muslims, the means to actually commit the crime, such as explosives or weaponry, were in fact provided by undercover informants acting on behalf of the government, while only about 16% of investigations involving non-Muslim perpetrators utilized this controversial tactic, which critics have blamed for effectively manufacturing criminal conspiracies in many cases.

“What was really interesting is that in the majority of cases involving people perceived to be Muslim, the perpetrators were not acquiring weapons on their own, but were instead being provided with them by government agents — yet they were being charged more heavily,” said Carey Shenkman, also a fellow at ISPU and co-author of the report. “Meanwhile, in cases involving non-Muslim perpetrators, you very often had people actually making explosives and stockpiling firearms. They didn’t need the FBI to go over and hand them weapons, because they already had them.”

In 2014, Mohamed Osman Mohamud, a 21-year-old Muslim man in Oregon, was sentenced to 30 years in prison after being convicted of plotting a bombing. Government informants had encouraged Mohamud and provided the actual materials for the attack. Last fall, a North Carolina man named Michael Christopher Estes, who wanted to “fight a war on U.S. soil,” attempted to bomb an airport in North Carolina. In January, he pleaded guilty to unlawful possession of an explosive device, a charge that carries a maximum penalty of up to five years in prison. A sentencing date for his case has not yet been set.

Estes’s case barely registered in the national media, nor was it promoted by political leaders who often use acts of violence committed by Muslims or Latinos to rally their bases around issues of immigration and national security. The disparity in sentencing in these similar cases is attributable, in part, to the charges they faced. The ISPU study found that the government is more likely to prosecute Muslim defendants for possessing “weapons of mass destruction,” a far more serious charge than simple possession of explosives.

Media scrutiny of cases involving Muslim defendants has been similarly unbalanced over the years, according to the report. The ISPU researchers analyzed coverage by The New York Times and the Washington Post from 2002 to 2015, finding that thwarted cases of ideologically-motivated violence involving Muslim perpetrators received, on average, 770 percent more coverage than similar cases involving non-Muslims, while completed violent acts were covered twice as much. Last year, researchers at Georgia State University found that violent attacks involving Muslims received, on average, 4 1/2 times more coverage than those committed by non-Muslims.

This increased media attention also appeared to be helped along by government efforts to promote awareness of some cases rather than others. The ISPU study found that the Justice Department was, on average, six times more likely to issue press releases about foiled plots of violence involving Muslims than non-Muslims. Reporters often use these releases in their news stories following such incidents, using a summary of the government’s allegations and taking note of the harm that foiled plots could potentially have caused.

This disparity in media and legal attention to cases of ideologically motivated violence has grown more troubling with the increase of violence carried out by sympathizers of the “alt-right” movement over the past several years. More than 100 people have been killed or wounded in the U.S. since 2014 by people believed to have been supporters of the “alt-right,” according to a February 2018 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Despite these acts of violence, however, the Department of Homeland Security under President Donald Trump has been working to strip funding from groups that work to mitigate far-right violence, while redirecting counter-extremism programming to focus exclusivelyon Muslim terrorism.

Despite increased number of acts of violence by far-right and white-nationalist movements, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security under President Donald Trump has been working to strip funding from groups that work to mitigate far-right violence, while redirecting counter-extremism programming to focus exclusively on Muslim terrorism.

The disparities documented in the report help quantify a level of institutional bias in the legal system and media that many have argued exists in cases involving Muslim perpetrators. The glaring differences in response to very similar acts of violence suggest that systemic biases have warped the way in which these institutions are functioning, leading to vastly unequal treatment of individuals based on their personal background, as well as inappropriate or excessive policy responses to perceived threats.

“At heart, there is a question here of what we as a society deem threatening, and what we as a society are afraid of. What you often find is that when a crime is committed by a member of the dominant, privileged group in any society, it’s excused as an aberration, while crimes committed by members of an out-group are pathologized toward that group as a whole,” said Dalia Mogahed, the director of research at ISPU. “This implicit bias finds its way into all our institutions, including courtrooms and the media.”

“It’s a self-perpetuating problem, and until we address it and stop making excuses, it’s not going to change.”

This article was published by The Intercept on April 5, 2018.