Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry presents serene Iranian landscapes amid a protagonist’s grim ideation. The protagonist drives through Iran’s mountainous gravel roads, attempting to locate someone to burry him following his intended suicide in exchange for a generous fee. An affluent Mr. Badii recruits a few men, who embrace diverse social and ethnic backgrounds, to fulfill this earnest request. He drives them through the same arid streets of Tehran as the men offer their unsolicited response to the age-old question: what is the purpose of life?

Taste of Cherry leaves the viewer anxious to learn of the protagonist’s precarious life status. While the viewer clings to Mr. Badii throughout his endeavors, several issues remain superficial. The film never reveals what drove Mr. Badii’s suicidal ideation, neglecting the personal details of his life. The first time the audience learns of his name is when he outlines the steps the men should take in the morning following his suicide attempt.

The protagonist pleads for the recruited men to meet him at his dug-up hole at dawn and shout his name: “Mr. Badii, Mr. Badii.” If he fails to respond, he asks they toss twenty “spadefuls of earth” into the grave and take the 200,000 tomans (Iranian currency) he left in the car. If he does respond, they must assist him out of the burial site, the 200,000 tomans still awaiting their possession. He navigated through Iranian roads, enlisting random men for their assistance. The first two men, a young Kurdish soldier (Afshin Khorshid Bakhtiari) and an Afghan seminarian (Hossein Noori), refuse to assist. However, Mr. Badii eventually manages to convince an Aziri taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri) who is in desperate need to finance his child’s medical bills.

Despite his deliberate efforts to trivialize his request, the various characters sought to dissuade Mr. Badii’s grim decision, each leaning on rationale from religion to lived experiences. The Afghan seminarist responded to the protagonist’s confusion on why he chose to attend a seminary in Iran, disclosing he had to flee Afghanistan because of the war. The taxidermist revealed he once intended to end his life before “a mulberry saved [his] life.”

As Mr. Badii drives each man through the Tehranian roadway that leads to his chosen grave, the viewer’s attention turns to the landscapes that peak through his car window. Kiarostami, the film director, captures Tehran’s working class, guiding the audience through the capital’s construction sites and infrastructure projects. He also catches the rural population reciting traditional melodies and echoing Iranian proverbs among lush slopes and desolate pathways. Kiarostami strategically weaves the laborers to the capital’s distinguished terrains, illuminating the pair as harmonious and integral through the clouds of dust the car leaves in its trace. The Iranian scenery assumes a third presence in the vehicle. While the background offers a glimpse into the lives of the working class, the conversations between Mr. Badii and the men he encounters further unveil the details of their lived realities. Taste of Cherry’s candid display of its laboring class contrasts against Mr. Badii’s (Homayon Ershadi), the film’s protagonist, melancholy.

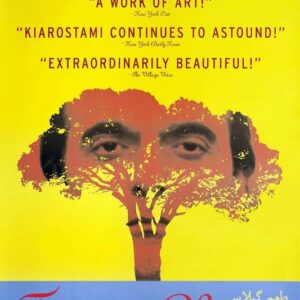

However, before its release, the cast, crew, and script underwent a scrutinous process to ensure the film aligned with Islamic cultural values. Iran’s stern opposition to Western media, as well as its suppression of conversations concerning the sinful deed of suicide, threatened the film’s release. Despite Taste of Cherry’s precarious status, the film received global praise, and international success; the film gained such recognition such that it received the Palme d’Or in 1997 (the year the film was released), the most prestigious award offered at the Cannes Film Festival.

Taste of Cherry views like a poem. It explores an impassioned plot saturated with ambiguities. Kiarostami navigates through Iran’s strict state censorship laws and turns to “surreptitious ways of expressing” Iran’s social and political reality. In the film’s ending, Throughout the film, Kiarostami shifts to the protagonist’s perspective, presenting point-of-view shots that intensify the viewer’s connection to the protagonist despite his aloofness. Taste of Cherry is melancholic yet captivating, leaving the viewer wondering if Mr. Badii will abandon all life has to offer. Or, as the taxidermist phrased it, whether Mr. Badii is prepared “to give up the taste of cherry.”

Discussion Questions:

- The film offers a glimpse into Iran. What did you observe about the country (i.e. its landscapes, people, culture, working class)?

- In an interview, Kiarostami mentioned he believes “that those films which appear nonpolitical, such as poetic films, are more political than films known specifically as ‘political’ films.” How does this quote relate to the film? In what ways do you see Iran’s politics bleed into the plot?

- Research Iran’s media censorship laws. In what way did it impact the film, whether implicit or explicit?

- How did you interpret the ending? Did you find it satisfying? Why or why not?