As Women’s History Month comes to a close, the Middle East Policy Council (MEPC) had the pleasure of interviewing Helen Zughaib, a renowned DC-based artist from Lebanon. We had the opportunity to discuss Helen’s story of escaping civil war, moving to new countries, finding her identity, and learning what it means to create empathy, an open space for dialogue, and combat stereotypes of Arabs through the power of paints, brushes, and canvas.

Helen’s work has been widely exhibited in galleries and museums in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East. Her paintings are displayed in private and public collections, including the White House, World Bank, Library of Congress, US Consulate General in Vancouver, the American Embassy in Baghdad, the Arab American National Museum in Detroit, the Barjeel Collection in Sharjah, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the DC Art Bank Collection.

Her work has been included in Art in Embassy State Department exhibitions abroad, including Brunei, Nicaragua, Mauritius, Iraq, Belgium, Lebanon, Sweden and Saudi Arabia. Helen has served as a Cultural Envoy to Palestine, Switzerland, and Saudi Arabia. The John F. Kennedy Center/REACH has selected Helen as a member of the 2021-2024 Inaugural Social Practice Residency. Her paintings have been gifted to heads of state by President Obama and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Helen grew up in a constant state of motion, her early years defined by evacuation, displacement, and separation.

Born and raised in Beirut, Lebanon’s capital, she was forced to leave after the outbreak of the 1967 Six-Day War between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, and again in 1975 due to the Lebanese Civil War. During these periods of uncertainty, she lived in Kuwait, Greece, and Iraq at various times.

Then, Helen and her family had to permanently leave their home in Lebanon when she was 16 years old.

“When we left, it was under curfew. We literally left everything and just ran out of our flat because there was going to be a shootout from two different militias,” Helen recounted.

“We were sleeping in the corridor and then the concierge at the building, who had been watching what was going on [outside], came to my father and said ‘you need to go, right now,’” Helen continued.

Her family sought refuge in Paris. The difference between her life in war-torn Beirut and the new experience of Paris was stark.

“[In Paris,] we didn’t have the war to think of. We had cultural differences between freedom for me as a young lady at 16 and 17. I was permitted to do things that I would never have been able to do prior,” Helen said.

Though away from the looming threat of war, the move didn’t quickly rid her of anxieties and fears.

“I was so traumatized by all that had happened that I was scared to walk around the block in Paris, thinking I would never get home. I was scared something would happen,” Helen said.

What ended up “saving” her in the brand new city was her family home’s close proximity to a small museum called Jeu de Paume (has now been relocated and largely expanded).

“In school, I was studying in my art history class, and I just fell in love with Claude Monet. Then I found that I could see his paintings out of the history books and in real life, up the street from where I lived,” Helen said.

“So I began cautiously going up there. It became my place where I could go and sit and feel at peace in this tiny old museum. To me, it was a sanctuary,” she continued.

Her frequent nearby museum visits inspired and shaped the interest in art that would influence the rest of her life.

“I thought, this is what I’m going to do. I am going to study painting,” Helen said.

That time in Paris, through much introspection, resulted in a new path and a focus on art.

Looking back, she recalls moments when she didn’t appreciate experiences as much since she was young, such as having her university art portfolio reviewed on a bench in the Louvre Museum. She “was living in history books, especially in Iraq and in Paris.”

“That is all somehow inside of you, like a little container, and then it comes out at certain points. You can feel these elements of color and patterning, which is what I grew up seeing and absorbing in some subconscious way, which turns into a sort of style,” Helen said.

She then moved to the U.S. to attend Syracuse University and study visual arts and performance, gradually commencing her extensive art career.

Helen doesn’t describe her artwork as political but more as responsive, a reaction to something that is happening outside of her studio.

“As an artist or writer, you respond to what’s happening. I didn’t make the war, I didn’t make 9/11, I didn’t make January 6, but we respond,” she said.

When asked about the role of art in bringing attention to real-world challenges, Helen highlights Pablo Picasso’s Guernica.

Guernica was painted in 1937 as a response to the bombing of the Basque town of Guernica under the rule of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War.

Helen explains how she sees political art as responsive art by illuminating an anecdote from Picasso: “[The painting] was still in Picasso’s studio, and a member of the occupation forces heard about it and wanted to see it firsthand. He [the officer] came to Picasso’s studio, saw it, looked at Picasso, and said ‘ah, so you’re the one who did this.’ Picasso looked at him and said, ‘no, you’re the one who did this.’”

“I say that. Don’t call me a political artist or whatever, you made that mess,” Helen continued.

She describes her approach to responsive art on topics like the Lebanese Civil War, Palestinian occupation and displacement, and specifically the Syrian War, as her father was born in Syria’s capital, Damascus.

Her Syrian Migration Series, a group of over 50 paintings, was inspired by African-American painter Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, which depicts the migration of African Americans from the rural South to the metropolitan North.

“If you go to the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, there are thirty of his panels on the movement of African Americans…after the great war for reasons of Jim Crow, segregation, and drought. I kept seeing all these parallels [with Syrian migration],” Helen said.

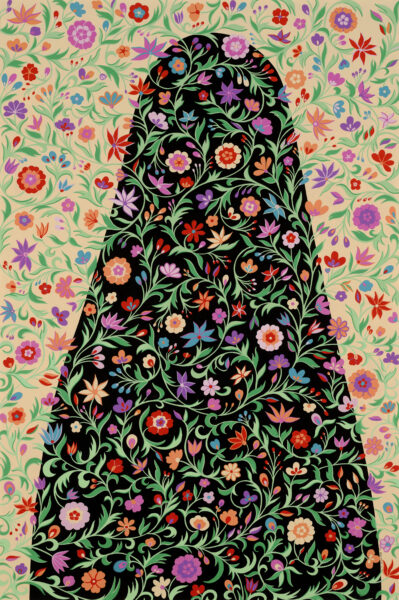

Helen describes her stylistic element of beauty in what she is depicting so that it won’t be aggressive for viewers to come see her paintings. Her pieces about heavy subjects are typically colorful, patterned, and attractive to the eye.

“If it’s repulsive and horrifying to look at, it’s very hard for people to see it and then come away with something,” Helen said. “Your immediate reaction is to not look. I think that’s human nature.”

Specifically, she recounts a previous installation at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., where she painted more than 30 pairs of children’s shoes in vibrant colors and designs.

“I started painting them at the height of the Syrian Civil War, where 13 million people were forced to leave in such a short time, going to Turkey, going to Lebanon, going to Germany, going anywhere [they could],” she explained.

“I thought about their shoes, and what is in store at the end of their travails and their journeys. I thought about Dr. Seuss’s book Oh, The Places You’ll Go,” Helen continued.

She described how children have and should have many dreams ahead of them, such as at one’s graduation, thinking about what awaits them.

“What exactly are these [Syrian] kids’ dreams? Fleeing from their home, going into a refugee camp? Being born into refugee camps?” Helen said.

So she named the installation “The Places They’ll Go.”

“When you don’t know the background of what I’m going for, people see ‘oh, cute shoes, maybe my child could fit into these shoes.’ You just see little shoes painted and beautiful and will attract your attention,” Helen said.

“So I’ve succeeded in getting you to my shoes. Then you can read my art statement on what I’m really telling you about. But I got you there in the first place, which is half the battle. Instead of just turning around, not listening to me, and not looking,” Helen continued.

Her shoe art collection is an ongoing installation.

Her newest piece is called Amal, or ‘Hope’ in Arabic. Painted in white, black, red, and green, it is a tribute to the children of Gaza, of whom 20,000 have been orphaned in less than six months, according to UNICEF.

“What is unfortunate in what I’ve been seeing with people that I know, both writers and visual artists, is the censorship on this current issue [in Gaza] and the backlash,” Helen said.

She does not see this type of censorship in other pieces of hers. Contrarily, her paintings regarding Syria were very well-received, having been shown twice at the Kennedy Center’s Hall of Nations.

“It’s interesting to see the ability to examine that [Syrian] issue as opposed to currently [the Palestinian issue],” Helen said. “I know at some point, it may not be right now, but we’ll get to that point where it will be portrayed by artists just like Guernica and will show a period of time for people in the future to say ‘okay, let’s not have that happen again.’”

“Because after all, what is the darn point of it all? Do I think we will learn? I’m not sure. Look at Guernica, he painted that in 1937, and yet we have it today. We have it in Syria, in Sudan, in Ukraine, in Haiti. That’s something I don’t understand but I think that some people do. That is the importance of creating art, even if it’s going to be censored. At some point, it will not be.”

She believes a way for art to positively affect current political events is by acting as a dialogue and a way to build cultural bridges and connections.

“I don’t want to tell you what to think. I want a dialogue that engages both sides. I may not change your mind, but at least you can’t hate me or you can’t put me in that box again,” Helen said.

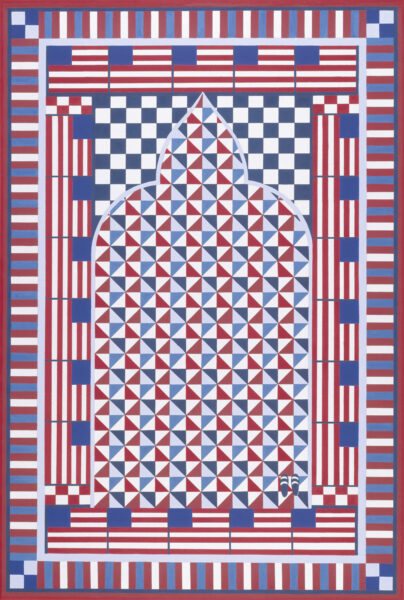

Exemplifying this nature of cultural connection, her career in the U.S. took off exponentially with her painting “Prayer Rug for America.” The painting began a large trajectory into her career path.

“After 9/11, I personally experienced very unpleasant things here in Washington. That really shifted a lot of things in my career. The first piece that they [the Library of Congress] acquired was a piece that I did as a result of 9/11 called ‘Prayer Rug for America,’” Helen said.

“[This painting] showed a need to have a story talking about Arabs, Arab-Americans, Muslim Americans, in a different way, certainly, than was being advocated. The negative stereotyping after 9/11 was massive. Did I set out to do that? No, but that event happened, so I would say that that’s a very important painting in my career as an artist.”

The exhibition started in D.C. and then traveled for several years around the world. Helen aimed for viewers to see the painting as a place of introspection, as a place to think.

“I don’t want you to come in with your preconceived notions, your stereotypes, and your ideas of who Arabs or Arab-Americans are,” Helen said.

“Come in and just think about this for a second and open this dialogue, even if it’s a little tiny agitation towards some connection, some little brief moment, a spark of this idea that you’re a human being and I am as well. Let’s have this connection,” Helen continued.

Helen related this painting, aiming for individuals to learn and unlearn generalized stereotypes, to her experience as a cultural envoy to Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, and Palestine.

In Switzerland, she attended different schools and spoke with young people who migrated from various countries such as Afghanistan and Libya.

Helen described one encounter: “We shared very intense stories about ‘how did you get here?’ One man drew me a picture of one of those dinghies trying to cross the Mediterranean from Libya, he drew it in pen and he was showing it to me and he made this mark over and over again in this one particular spot on this boat, and I said “what’s that?” He responded, ‘that’s where I was sitting.’ He wanted to give me his drawing and I said ‘no, I’ll take a picture of it. This is for you, this is your story, this is your life.’”

When she looks back at her portfolio, she believes that the body of work that best exemplifies who she is is a collection of 25 paintings titled Stories My Father Told Me. The paintings are stories Helen’s father told her and her siblings when growing up.

“It’s used almost as part of education, to continue education, what’s important in the family, in the extended family, and in the village itself. How you’re responsible to your community, regardless if it’s your family, your environment, the land, or the traditions,” Helen said.

She feels that her paintings inspire a deep longing, a yearning desire to go back to a place that one used to know but can’t return to.

“[It encompasses the] place that I was born, the place that I was forced to leave. When you are forced to leave your home, you end up with a nostalgia where it’s almost like a dream. Even the bad parts are like a dream,” Helen said.

She emphasizes the importance of sharing stories to learn from each other.

“I find that through that storytelling, that level of connection can happen without acrimony. It’s not a political speech…It’s something that we share regardless of where we come from, or left, and bring,” Helen said.

When thinking about what advice to give to young girls, she quickly and confidently stated that everyone has a story, something worth sharing.

“If you can come up with a way of depicting your authentic story—writing, visual, dance, music—I want to hear it because I want to learn what your story is. You tell it to me in a good way, you do your homework, you go to school, you want to do it? You learn how to do it. Learn how to create and execute it in a way that draws me in, one way or another, so that I want to sit down and hear what you have to say,” Helen said.

“Art has a way of rippling out and making these connections and, all of a sudden, your story is not just your story—so many people can relate to it,” Helen continued.

You can find more information regarding Helen here: https://www.hzughaib.com/

All photos listed above excluding the headshot are Helen Zughaib’s paintings.