A rhythmic trill pierces through the Si Belle beauty salon. Jamale (Gisèle Aouad) cups her hand and raises it to her upper lip, performing the traditional Arab ululation. As people walk past the cinderblock building adorned with graffiti and faint remnants of peeling paint, the wavering shriek from the dusty pink unit signal a celebration. Inside the salon, three friends playfully honor their bride-to-be friend, dancing freely and bestowing a lump of aluminum foil-turned-crown atop her head.

To the common eye, the location looks far from a venue for festivities—the cursive letter “B” from its overhead sign left slanted as though abandoned, and years of dust and debris stained the exterior walls with a pigmented brown. However, this Beirut beauty salon is a sanctuary for feminine rituals, from haircuts to sugar waxing, an intimate space for therapeutic relief from social obligations. It bears an essence of tender camaraderie and contagious joy that extends to the viewer.

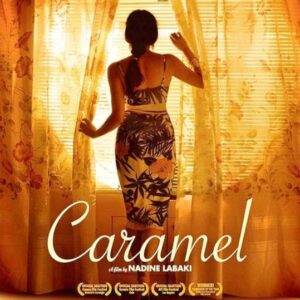

Nadine Labaki’s debut film, “Caramel,” sets aside politics and offers a sweet glimpse into the mundane lives of five Lebanese women linked through a beauty salon. This 2008 film, told with a comedic twist, explores their daily challenges and individual narratives. The salon’s owner, Layale (Nadine Lebaki), is desperate for love, entangling herself in an affair with a married man. Her employee, Nisrine (Yasmine Al Massri), is set to marry her prince charming. However, he does not know she is not a virgin. Another salon employee, Rima (Joanna Moukarzel), tackles her sexuality in a society that preserves heteronormative ideals. Jamale, a regular customer, grapples with her declining years, striving to amuse herself with a failed acting career instead. Finally, the film examines Rose (Sihame Haddad), a full-time seamstress who occasionally visits the salon to address the mischiefs of her mentally ill elderly sister, Lili (Aziza Semaan). As she devotes her life to caring for her sister, Rose’s values come into question when a client expresses a romantic interest in her. “Caramel” documents the five women’s day-to-day lives as they navigate through their personal challenges.

The dramatic comedy captures the Lebanese women in love. As the title, which refers to an epilation method of concocting sugar, water, and lemon, implies, love is sweet and tangy. However, like peeling wax off the body, it stings, leaving a residue of sugar-coated pain.

Although at times impractical, the protagonists allow themselves to love modestly yet unconditionally, the audience identifying with the film’s authentic portrayal of dynamic relationships, romantic and platonic. Despite her old age, Rose found herself in a wholesome yet short-lived love affair. In a society that denied her the conventional love experience, Rima shared intimacy with another woman through the simplicity of mundane moments. Although “Caramel” remains mindful of the characters’ social burdens and obligations, it allows the women to love, engage in its vulnerable sacredness and receive it all at once. “Caramel” challenges prevalent media that deny Arab populations a narrative separate from war and political tragedies, capturing Arab joy.

The film concludes with the words “To my Beirut” plastered on the screen. The film reads like a love letter to the Lebanese city. Illustrating their diverse stories and realities, Nadine Labaki honors the citizens who built and dedicated their lives to Beirut. She presents their desire to love—intensely and unapologetically. She explores the staunch sisterhood between the film’s protagonists, mirroring the collective devotion Lebanese women unfailingly demonstrate within their friendships. Lebaki’s “Caramel” documents the Beirut she adores and cherishes, illuminating what mainstream accounts often neglect. Her warm cinematography captures glimpses of Beirut, showcasing its narrow streets garnished with concrete buildings and sporadic trees. It offers a sense of nostalgia and familiarity, transporting the audience to the pastel-pink beauty salon in Lebanon’s bustling city.

Discussion questions:

- How does “Caramel” capture the roles of women in the MENA region? How do their obligations compare and contrast with those of women in the “West”?

- What do you think of Nadine Lebaki’s decision to decenter politics? Why do you think she chose to do so?

- Did you find the ending satisfying? Why or why not?