As the world becomes more connected than ever through globalization and social media, security has become an increasingly important aspect of governance and regime survivability. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a small yet important global hub for innovation and business. The nature of the UAE’s demographic, which is composed of less than twelve percent native-born Arab citizens, with expatriates and migrant workers accounting for the rest of the population, has made national security a priority on the state’s agenda. UAE leadership decided against the conventional route of a physical police and military presence, and opted instead for increased surveillance through a diverse fleet of technology.

In 2019, according to an official from the Abu Dhabi Monitoring and Control Centre, a government department established by Abu Dhabi’s Executive Council, there were more than 300,000 security cameras watching over the city’s 1.5 million residents. The launch of the ‘Falcon Eye’ system in 2016 expanded the geographic coverage area and “built partnerships with local and federal establishments to support and enrich databases” to enhance monitoring standards and data analysis. Traffic management is one objective of surveillance, but a robust digital security network also allows the state to monitor and inhibit problem behaviors. Although information on Dubai is less accessible, in 2015, the director of the International Centre for Security and Safety at the Dubai Police Academy announced that there was a camera on every street corner and claimed that the “whole city is covered.” At the time of that interview, there were 3,000 cameras installed at the Dubai airport alone.

The Modern Watchtower

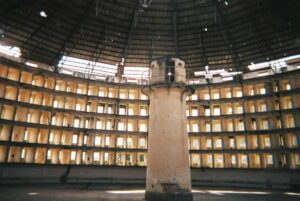

As a response to perceived domestic and international threats, the UAE security apparatus has resorted to the use of ubiquitous surveillance technologies. One way to understand this strategy is through Michel Foucault’s “power/knowledge” concept. Foucault was a 20th-century French philosopher whose theories explored the relationship between power and knowledge. He argued that governments and other social institutions use both to enact social control over the population. A famous metaphor used by Foucault to demonstrate his theory is English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s 1787 Panopticon. The panopticon is a circular prison designed to expose every prisoner to the scrutiny of a central watchtower, which was positioned so that individual prisoners would never know when they were being watched.

The updated version of the theory in the UAE shows how CCTV surveillance and monitoring is intended to sustain the government’s control and power by gathering data and information about its public. The Emirates is believed to possess one of the highest per-capita concentrations of surveillance cameras in the world and has religiously embedded the notion of knowledge as a form of power in the country’s security apparatus.

There has been substantial debate about whether this extensive surveillance network constitutes an encroachment on people’s rights and civil liberties, but proponents point out the upside: the UAE’s security forces have apprehended criminals and solved crimes more quickly because of its robust monitoring system. The assassination of Hamas commander Mahmoud al-Mabhouh at a Dubai hotel in January 2010, and the fatal stabbing of an American school teacher at an Abu Dhabi mall in 2014 were both captured on CCTV cameras. In the aforementioned cases, surveillance was used as a reactionary tool, but the primary purpose of the UAE’s surveillance strategy is to create a sense of self-policing, similar to the panopticon, where people feel watched and monitored, and therefore, abide by laws and the social contract without question.

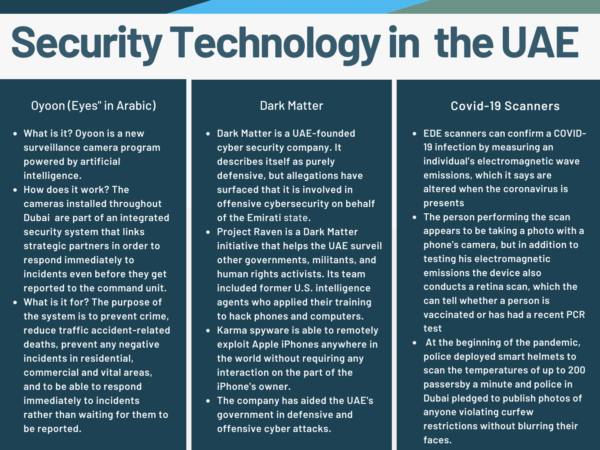

The UAE has also exponentially grown the government’s reliance on technology as it pushes to become an artificial intelligence government that is able to perform all governmental services and interactions digitally and online. Although it makes government operations more efficient, it makes them more vulnerable to cyber-attacks. Therefore, the UAE has invested heavily in cybersecurity and surveillance to combat the impacts of digitalization.

In addition to the concerns voiced about the UAE’s hyper surveillance, mandates associated with curtailing the spread of Covid-19 have given the UAE justification to further employ its surveillance mechanisms as a containment method. The government has adapted the use of pre-existing software to check people’s temperature and monitor gatherings. The pandemic has afforded the government a heightened degree of power over people’s movement and interactions, once again blurring the lines between the private realm and state control over movement and access.

The impact of Covid-19 triggered the development of new surveillance and tracking software that caused UAE’s surveillance system to grow larger and more pervasive. Beyond the scope of the pandemic, rising domestic and international threats to the country have bolstered the government’s pursuit of security measures to counteract such risks, causing concern that hyper surveillance will become a fixture of Emirati policy. Under Foucault’s power/knowledge construct and the analogy of the panopticon, those under surveillance eventually fall into line and police their behavior without any direct intervention of an authority figure. Whether people in the UAE – and under other hyper-surveillance states around the world – accept constant monitoring as a necessity of modern life or reject the incursion on their privacy is still to be determined, but an institutionalized surveillance policy has the potential to drive away investors and expats who view the policies as an over-step.

Examples of UAE Surveillance Technology

Questions for Reflection

Questions for Reflection

- What do you think? When does surveillance cross the line into an invasion of privacy? Does the collective good outweigh personal rights?

- What technology does the government in your town, state or country use and for what purpose? Public safety? Education? Health? What are the benefits and drawbacks of such tools?