Let’s take a visual tour of two exquisite sixteenth-century Persian paintings, “A Camp Scene” and “Nighttime in a Palace,” from the collection of the Harvard University Art Museums. These two paintings not only are examples of incredible artistic virtuosity but also contain a wealth of social detail that illuminates urban and rural life, and, indeed, some of the purposes of secular art in Muslim society. The two paintings are both attributed to Mir Sayyid ‘Ali, a well-known painter who flourished at the Safavid and Mughal courts around 1550-1574 CE. Incredibly, given the level of detail of the paintings, they are each only about 28 cm by 20 cm.

Click on the miniatures below to enlarge them and zoom in on details:

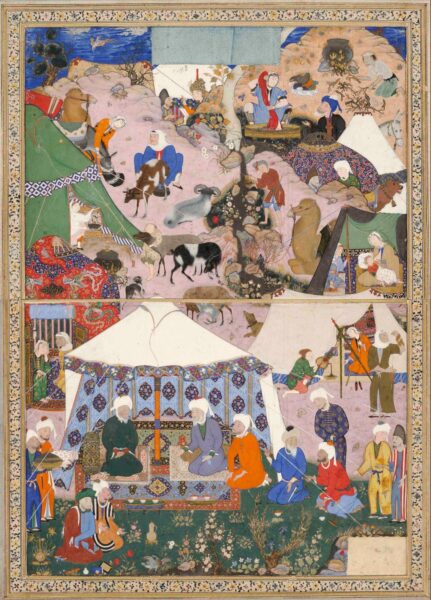

A Camp Scene

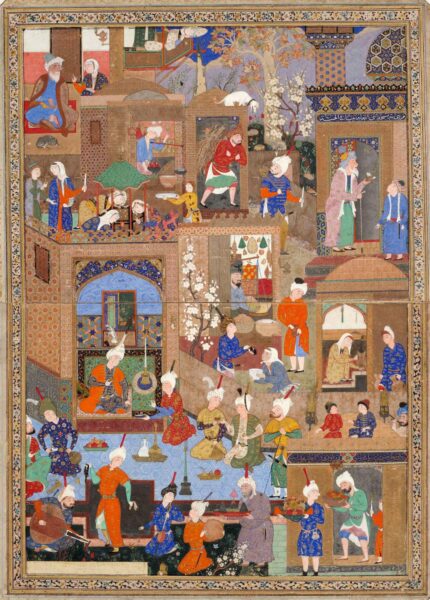

Nighttime in a Palace

GENERAL QUESTIONS

While looking at these two miniatures, try to answer the following questions:

- 1. How is this image composed (placement, color, and general organization of the page)? Can you point out people, words, repeated motifs?

- What is the main action or story? Is it a rural or urban setting? How can you tell?

- Who are the main characters and what are they doing? How are they dressed? Can you tell what their status is?

- What elements does the artist repeat? What do you think he is trying to convey?

“A CAMP SCENE” ANALYSIS

The scene shows a nomadic encampment of nine tents of different types and colors. There are four low, long traditional Arabian tents, called tunnel tents (except that traditional ones are generally black). One tent is a rarer type, cone shaped and white. Several yurt-type tents are made with richly patterned textiles; you can see how the latticed frames are constructed at the top of two of them.

There is a lot going on in this small painting. We can count twenty men, ten women, two children, and one infant all engaged in different activities. Have students find all the plants and animals depicted—there are two camels, two donkeys, two shepherds, one lamb, one goat, one cow, one ox, one dog, one cat, one duck and two birds! Can you identify any of the plants? The artist’s name appears faintly on the uppermost center white tent.

In the largest tent, two older bearded men sit on luxurious carpets. If we compare this tent with the others, we can see it is the most ornate. This is the main “story” of the painting. On the right side of the two men, who appear to be the main actors, there are three men seated diagonally, two of whom are engaged in conversation. On the left side, we see two other men seated on the ground. It is possible that there will be an exchange of gifts.

In Persian paintings, the style of the robes of these men and the strips of cloth under their chins would suggest that they are Arab nomads. We can tell that these seven men are equally important, as compared to the men standing behind and around them, because there are seven cups neatly lined up in front of the seven men (notice the lids on the cups, perhaps to keep the beverages hot or to keep the bugs out).

In front of the two men seated closest to the bottom of the painting are writing implements–books, a pen case and an inkwell are arranged on the grass. Based on these objects, we might infer that this is an illustration of a formal gathering in which a contract or an agreement might be signed, or these objects may simply be reflecting on the status of the men as literate.

In fact, the painting is probably a scene from the well-known folktale of Layla and Majnun, according to the analysis of Oleg Grabar and Mika Natif. It could have been used to illustrate a text, or as part of an album of miniatures. The story of Layla and Majnun speaks of the doomed love between Layla and Qays in Arabia, which led Qays to become mad, or “majnun,” and retreat into the desert to live with the animals. In the far right corner of the painting, we can see that there is a young man, removed from the activities of the painting, lighting a fire—probably Qays. Layla is depicted as the young women in the red tent decorated with the simurghs (mythological bird). In the poem of Layla and Majnun, there is a scene in which Qays’ father goes with his tribesmen to ask Layla’s father for her hand in marriage for his son, and this is the likely subject of the men’s discussion in the main tent here. Students might do further research on the story of Majnun and Layla, as well as the theme of endless yearning in Islamic literature.

Look at the carpets, tent walls and other textiles in the painting. Again, notice the incredible level of detail the artist has included in this small-scale medium. Can you see the calligraphy on the carpet in the main tent?Have students identify the different geometric and arabesque patterns and colors present throughout the painting in the carpets, the tents’ interiors and exteriors, and the clothing of the people. Let’s wander away from the main event to see what else is happening in our nomadic encampment. To the left and behind the main tent, we see a beautifully dressed woman and her maids in a red tent painted with simurghs. In Persian legend, the simurgh is a large, winged creature that looks a bit like peacocks. They have the head of a dog and the claws of lion, and live near the water. It is said that the simurgh has lived so long that it has seen the world destroyed and recreated three times, and because of its long life, has universal knowledge. An extended activity might be for students to research the simurgh and other characters in Persian mythology.

Many other activities typical of a nomadic camp go on all around. In the tent to the right, a woman (who has carefully placed her shoes at the entrance to the tent), waits for a servant to pour water. Notice that the water here and elsewhere in the two paintings is black—in fact, the water is painted with powdered silver, which has tarnished to a black color over the centuries! The old woman on the right is spinning yarn with a drop spindle. Have students think about the connection between the many beautiful tents, carpets and fabrics in the painting and the nomadic lifestyle—how the wool and other products from sheep and other animals form the basis of the nomad economy and lifestyle. Can you give other examples of this? Think about, for example, two typical dishes from nomadic cultures in the Middle East—kebab and yogurt! Note the other examples of humans caring for their animals in the painting—a woman feeding a donkey, another milking a goat, a boy with his arm around a sheep.

Looking at the different people in the painting, think about how the artist represents their relative position in society. How can you tell (through positioning, activity, clothing, accessories, etc.) the status of the various people in the picture? One interesting element in this miniature is the way the artist displays his talent at depicting human diversity and emotion as well as the complex decorative beauty of everyday items. Notice the tender looks exchanged between the woman and the baby she is nursing in the tent on the right. Look at the woman washing clothes in the upper right of the painting. She wrings out a large piece of cloth as she sits in front of a large basin of gold, and the clothing she has already washed is piled behind her in a beautiful Chinese blue and white porcelain dish. It’s doubtful that even the richest nomads would wash their dirty laundry in gold and porcelain—why do you think the artist depicted them in this way? His virtuosity in depicting these items of conspicuous consumption, like his depiction of the range of very human activities and the delicacy of the tiniest details—the henna designs on the women’s hands and feet, the guy ropes on the tents, even the hairs on the camels’ lips—would have impressed his patron and audience.

One final interesting element in this painting is the influence of Chinese aesthetic culture. Notice the way that the rocks, clouds, birds and trees are represented. Can you find similar examples of these stylistic elements in Chinese painting?

“A Camp Scene” captures a not only a vivid moment in the story of Layla and Qays, but opens a window for us into the life of Middle Eastern nomads through its illustration of the various people, animals, plants, artifacts and activities.

“NIGHTTIME IN A PALACE” ANALYSIS

The second miniature, “Nighttime in a Palace,” takes us from the rural scene in “A Camp Scene” to a vivid urban cityscape, showing us a different aspect of social life in the Safavid Empire. This painting has three separate sections—a princely garden pavilion, a city street and a domestic interior in the upper left corner. The court pavilion in the lower left is defined by low walls and a window overlooking a garden. A young prince seated in an iwan (a vaulted space opening to a courtyard on one side) wears an elaborate cone-shaped white turban with a white feather.The scene is of a feast—courtiers offer the prince and one another delicacies and (presumably) wine from beautifully decorated platters and ewers (pitcher/jug), while servants bring out even more plates of fruit from the kitchen in the lower right, assisted by a young boy carrying a candle. What fruit can you identify on the platters?

Four young male entertainers play instruments and dance at the bottom of the scene. These instruments are, from right to left, the ‘oud (stringed, lute-like instrument), the kamancheh (Iranian bowed string instrument), and the daf (large Persian frame drum). Students might do research on Middle Eastern musical instruments to identify the instruments pictured here, and listen to the type of music being played.

In the bottom left of the pavilion scene, two men sit drinking with a pen case and a key in front of them. These are a bit mysterious—can you imagine why the key and pen case are there? There are several observers of the feast. Directly above the prince, three women in elaborate clothing and headscarves lounge around a pavilion observing the goings-on below. To the right, two youths watch the feast and carry on an animated discussion on the roof of a domed building, perhaps the kitchens. The building has an inscription on blue tile by the famous Persian poet of the fourteenth century, Hafiz: “The pupil of my eye is your nesting place; be kind, alight, for it is your home”.

Let us follow the city street as it snakes upward, starting just above the domed kitchens. At a cistern with a spigot shaped like a lion’s head, a woman fills her jug while a youth waits his turn. Again, notice the silver water turned black over time—even tiny droplets splashing out of the woman’s jug. Continuing upward and to the left, we see a market scene with a courtier buying something from a woman with a bowl while another young man fishes for change in his wallet to buy something (perhaps a melon?) from the proprietor of a shop. Notice the scales and the variety of foodstuffs being sold: flour and bread in baskets in front of the shop, apples, pears, pomegranates, grapes and grape leaves. The details are extraordinary here, from the pattern on the customer’s tunic to the wood grain in the shutters of the shop.

Following the street up to the right, we come to an ornate mosque with a decorated dome and minaret. Above the doorway there is another calligraphic inscription, here a famous hadith, or saying of the Prophet: “He who builds a mosque for God, God will build for him a dwelling in Paradise”.

An extended activity for students might be to study the structure and designs of mosques in various Muslim societies. In addition, students might analyze this and other hadith and research the importance of hadith to Muslim social life, or perhaps learn more about the Arabic language and practice some Arabic calligraphy. In front of the mosque, an old man with a cane speaks to a young boy carrying prayer beads.

The street continues to the left with more engaging vignettes: a courtier with a mace strides forcefully along, looking back over his shoulder. A man carries a heavy load of wood, a dog on the roof barks at the people below, while another merchant weighs out pomegranates in a scale, perhaps for the boy with the empty dish. Past the women eavesdropping on the party below, another woman walks with a young boy who is speaking to her. Above this pair is an interesting domestic scene. We are now inside a house, where a woman and a white-bearded man sit talking. A cat lies curled up on the floor in front of them. To the right, a woman lounges on a balcony, gazing out over the scene below, nearly touching the branches of a large chinar, or plane tree.

The use of color and pattern is quite striking. Consider the use of hexagons in various places in the design. The floor of the pavilion is a simple hexagon tessellation in blue tiles. On the walls of the iwan, we see the hexagon pattern repeated, but here it takes the form of intertwined star forms, perhaps painted wood inlay. The outside wall of the pavilion has more hexagonal motifs. Can you find any other use of hexagonal patterning in the painting?

A major motif in the painting is the idea of light. There are nine different light sources in the miniature—can you find them all? What are the differences between the various lamps, candles and torches? Notice that these light sources are not used as in much Western art to cast shadows or illuminate the subjects differently, but rather to show that it is a nighttime scene and perhaps for some symbolic reasons as well.

Taken all together, this painting does not seem to illustrate any known story, although certain elements like the barking dog on the roof and the woman with the candle and the boy seem quite unique in Persian painting. Instead, the painting brilliantly depicts the variety and bustle of city and palace life, and the relationship between the palace, the urban merchant class, and other subjects. Moreover, we get a visual sense of royal architecture, public buildings and private dwellings and city life. It is likely that this miniature was painted by the artist as an exemplar of his talent—to demonstrate the repertoire of subjects and the exquisitely detailed composition of which he was capable. Perhaps he sought to attract a new patron or impress the court with his technical expertise and artistic prowess.

CONCLUSION

Our tour through these two splendid Persian miniatures demonstrates how much we can learn about the society and aesthetic tastes of a society through its art. When the society is as little known as that of the Middle East, the complex portrait of diverse peoples and activities and the exquisite artistic details in Mir Sayyid Ali’s two paintings can break down our stereotypes of the region and open a new window into learning about the Islamic world.

PROMPTS FOR FURTHER DISCUSSION

- What do the paintings show about the position and roles of women? Is it what you expected?

- How many of the plants and animals, real and mythological, can you identify?

- Identify any elements of the scene that are not “native” to the Middle East?

- Why might silks and ceramics with Chinese patterns be shown in an image like this?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Created at the Outreach Center at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies of Harvard University; originally published in the Middle East Outreach Council’s Perspectives newsletter and hosted on the Harvard CMES website. Lesson by Barbara Petzen and Negin Sohrabi, with advice by Mary McWilliams of Harvard University’s Sackler Museum.

Images from “A Nomadic Encampment”, folio from a manuscript of the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami, attributed to Mir Sayyid ‘Ali (Persian, 16th century), courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Gift of John Goelet, formerly in the collection of Louis J. Cartier [1958.75], photo by Photographic Services. Images from “Nighttime in a Palace”, folio from a manuscript, attributed to Mir Sayyid ‘Ali (Persian, 16th century), courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, Gift of John Goelet, formerly in the collection of Louis J. Cartier [1958.76], photo by Photographic Services, www.harvardartmuseums.org.

Grabar, Oleg and Mika Natif. “Two Safavid Paintings: An Essay in Interpretation,” Muqarnas vol. 18, pp. 173-202. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

Learn about the Ottoman miniature tradition at the Turkish Cultural Foundation.

Brief biography of artist Mir Sayyid ‘Ali

The Harvard University Art Museums website

The Freer and Sackler Galleries website. They have put together an excellent online guide to Islamic art.

Bloom, Jonathan and Sheila Blair. Islamic Arts. London: Phaidon Press, 1997.