Spoken languages have distinct styles

Americans use different words and speaking styles depending where they’re from and who their audience is. People on the West Coast and in the Midwest drink “pop, whereas in other places, people call the same beverage “soda” or “coke.” How we speak in the classroom is usually not the same way we speak with our friends. Language works the same way across the world.

The rise of the internet had a huge influence on how we communicate, and it made the transfer of information easier and faster. In the Middle East, people with access to technology learned about other ways of life and became aware of opportunities that they didn’t have. The internet also helped unite families separated by migration or conflict, and allowed Arabic speakers from different countries to connect with one another.

Technology changed communication in Arab society

Social media, in particular, has been a democratizing force in the Arab world. Up until the rise of the internet, entertainment and communication was dominated by cultural elites that largely perpetuated the use of the formal, classical Arabic. This dialect (click word to jump to dictionary below) is used in the Quran, in academia, and on newscasts, and differs significantly from the everyday language spoken in homes and on the streets.

On social media sites and in chat rooms, Arabic-speaking populations could suddenly speak to and entertain each other in their own dialects. But bringing Arabic online wasn’t easy: not only were these dialects spoken, not written, many websites weren’t able to accommodate Arabic script (most social media sites only added Arabic-supported versions in the late 2000s).

Adapting language to simplify communication

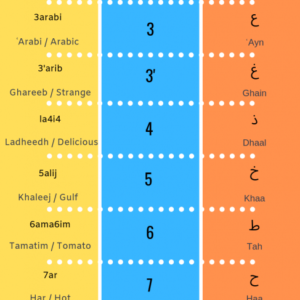

The solution Arabic-speaking youth developed was Arabizi, a method of transliterating Arabic with Latin letters and numerals to represent letters not present in English. The name is a portmanteau of the Arabic words for Arabic and English: Arabi + Englizi = Arabizi. Our chart illustrates the main innovation of Arabizi — the use of numbers to replace letters not translatable to the Latin alphabet. Arabizi also often incorporates simple English words like “hi” or “thanks.”

Although Arabizi arose out of the limitations of websites and electronics, it’s remained the main form of online communication for Arab young people even as these sites have come to support Arabic script. Arabic speakers use Arabizi for multiple reasons — young people feel it’s faster, more informal, trendier, and easier to type than formal Arabic. It also makes it possible to express things that formal written Arabic cannot, like gendered differences that are usually only detectable in spoken Arabic.

Easier to type and more expressive

For example, in the Levantine dialect men and women pronounce the letter “qaaf” differently, but this difference would be undetectable if a person writes it in Arabic script. In Arabizi, it is possible to provide the context that the writer is from Lebanon and female, or male and from the UAE. Arabizi also allows an expressiveness through capital and repeated letters that’s difficult to convey in Arabic script, and is essential to the exaggerated, over-the-top vernacular that’s popular on the internet in all languages.

Arabizi is also significantly easier and faster to type than formal Arabic because it doesn’t have a codified system of spelling. As a transliteration of spoken dialects, it relies on shared context between the people communicating and best guesses as to how something sounds — it’s virtually impossible to misspell.

Backlash from traditionalists

Not everyone appreciates the ease and expressiveness of Arabizi! The older generation in Arab countries have derided it as lazy, Westernizing, and a degradation of Arab identity and the language of the Quran. The Arab identity has long been intertwined with the Arabic language — in fact, the simplest definition of an Arab is someone who speaks Arabic. Classical Arabic is culturally significant as the language in which the Quran was delivered. Critics of Arabizi argue that it’s eroding the younger generation’s comprehension and respect of the traditional form. Some speakers of Arabizi agree that their ability to write in formal Arabic is weaker because of their use of the informal version of the language. And, much of the Arabizi-related research in the Arabic-speaking world has attempted to paint it as sloppy and disrespectful.

Arabizi also presents difficulties for researchers who gather information on social media, because Arabizi is so difficult to translate. It’s impossible to standardize the translation because of the variance of spelling across dialects. Innovative tools like the Yamli smart Arabic keyboard have attempted to bridge the gap, both for foreigners seeking to translate Arabizi into English and young Arabic speakers looking for help translating Arabizi into written Arabic.

Despite it all, Arabizi seems here to stay. Check out the video below by Lebanese pop star Nancy Ajram to see examples of Arabizi in action.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mWD96Rx5Ds

Article Keywords

Diacritics or diacritical markings are signs, such as an accent or cedilla, which when written above or below a letter indicates a difference in pronunciation from the same letter when unmarked or differently marked.

A dialect is a variety of a language that signals where a person comes from. The notion is usually interpreted geographically (regional dialect), but it also has some application in relation to a person’s social background (class dialect) or occupation (occupational dialect). A dialect is chiefly distinguished from other dialects of the same language by features of linguistic structure, such as word formation, sentence structure and vocabulary.

The Levantine dialect is spoken by the people in the area of the Eastern Mediterranean (the Levant) — Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Palestine, along with Iraq. It is important to note that each country has its own distinctions as well; for example, many Palestinians have incorporated Hebrew words into their vocabulary. People living in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya) speak a strain of Arabic that is influenced by the region’s indigenous populations and colonial histories (French, Spanish and Italian). Egypt is on its own, whereas the Gulf countries are usually mutually intelligible.

A portmanteau is a word that blends the sounds and combines the meanings of two others, for example motel (from ‘motor’ and ‘hotel’) or brunch (from ‘breakfast’ and ‘lunch’).

Transliterate means to write or print (a letter or word) using the closest corresponding letters of a different alphabet or language. Names from one language are often transliterated into another.

Additional Resources

In Arabic for Egyptian Youth: a Forgotten Privilege, the author talks about how the integration of English into daily affairs in Egypt has made younger generations lose touch with their native language and heritage. Proficiency in English or another second language is considered prestigious and believed to open doors of professional opportunities that Arabic can’t provide.

When a couple in Jordan tried to keep their infant son entertained with Arabic educational cartoons on YouTube, they noticed he became restless. But when they switched to English, the videos and songs captured his attention. “We could not find appealing Arabic videos for children that are both educational and fun. So we wanted to provide Adam with something that he would like and make him happy,” said mom Lubna. Thus, they were to come up with a project called Adam Wa Mishmish (Adam and Mishmish), an online cartoon show in Arabic which combines education and entertainment for children up to five years old. The website also offers accompanying programming in English!

An online collective, Bel Lebnééné, is trying to confront the huge linguistic difference between formal Arabic and Lebanese dialect. Bel Lebnééné aims to standardize a script for the local language and build a library of content. The collective aims to raise awareness and encourage Lebanese speakers to write and express themselves in Lebanese.

French, Arabic, Amazigh or Moroccan?! The incorporation of words and expressions from colloquial Moroccan into textbooks for primary schools, which coincided with the beginning of the new academic year, has broadened the debate about the paradoxes which Moroccans face between the languages they learn at home and those they learn at school. Indeed, the debate about the patois of everyday usage and the languages of the government administration and other official bodies has always been there. Moroccans are taught in Modern Standard Arabic or French – and sometimes in English or Spanish – while at home and in the street they speak Moroccan or Amazigh dialects. Whenever they deal with government, they are obliged to use French and when they receive communications from an official institution or official media they are written in Modern Standard Arabic. Read more about this linguistic divide in Morocco.

The language you would expect to hear in the United Arab Emirates is Arabic. Yet in a cosmopolitan place like Dubai, English is the language on the streets, in cafés and malls. Approximately 90% of the populations consists of expatriates so the Emirates is very much a multilingual society. As a result, native Emiratis struggle in their own mother tongue. Learn more about this dilemma and how the government is addressing it in a podcast from PRI.