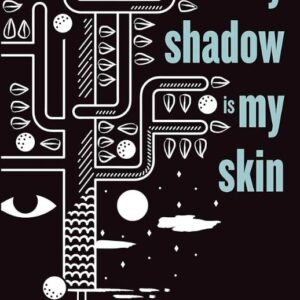

“I have taken my shadow—my Iranian heritage—and inverted it. My shadow is my skin. I advertise it” (p. 25).

In three declarative sentences, Iranian-American author Cyrus Copeland pledges his embrace to the one constant antagonist in his innate battle. He integrates his Iranian roots, which were once a source of delusion and shame, into his identity in a process that is distinct yet familiar to diaspora communities grappling with their hyphenated identity. In “My Shadow Is My Skin,” Copeland, alongside 31 other writers of the Iranian diaspora, guides the reader through personal narratives that reflect sentiments felt across the collective.

The anthology features the diaspora writers’ short stories, documenting their heightened disillusionment with Iranian leadership following the Revolution in 1979. Thousands of Iranians abandoned their lives in Iran and began anew in the US. The stories capture the consequential impacts, from incessant hate crimes to coerced estrangement, the writers, their parents, and their partners endured. Like all those in the diaspora, they ponder upon their sense of Iranianness and Americanness, deciphering whether the two can ever coexist. This anthology adds to the flourishing array of Iranian literature that clings to a past, culture, and country victim to contemporary conflicts. Divided into three sections, “My Shadow Is My Skin” captures the Iranian diaspora’s ventures of acceptance, integration, and continual yearning.

The first section, titled Light/Shadow, contains 11 short stories illustrating the authors’ journey of reclaiming their identity. They shed light on experiences that Western narratives have so long dominated. In his essay “When We Were Lions,” Mehdi Tavana Okasi recounts his encounters during his arrival in the United States as a political refugee. One line articulates the imperative nature of salvaging personal accounts: “This tension…between self and the world…is one that I’ve struggled with as I’ve come to understand the power of narrative” (p. 45).

In another essay, Jasmin Darznik details her mother’s response to learning she lost her virginity, further capturing the necessity to recount stories despite the time passed. When she was 18, Darznik’s mother made her “disappear.” The two moved to an apartment at the edge of town, miles away from friends, family, and any “American” influence. Years later, the author recounts the trauma and isolation she endured. She expresses: “But I tell what happened to me because, after all these years, I finally want to say that it is mine to tell” (p. 10; italics added). Both authors reclaim their individual histories, centering their voices and perspectives. In all stories included in the section, similar to the ones mentioned, the author finds solace in what used to leave them with discomfort. They grasp these experiences with an admirable sense of compassion and patience, forgiving those who shamed them for not meeting their conventional ideas of what it means to be Iranian.

Coding/Decoding, the title of the anthology’s second section, delves into what Amy Malek, in “Negotiating Memories,” termed the “alternating senses of belonging and exclusion” (p. 110). They navigate the intricacies of their Iranian and American identities, lamenting that they will never feel complete admittance. The authors vocalize their confusion and frustration as they split their loyalty between two nations at rivalry. In “Transmutations of/by Language,” Raha Namy communicates: “And trespassers who move in between countries/groups whose leaders come to identify one another as enemies are regarded as more of a threat” (p. 128). Namy, like all the other authors of this anthology, eventually accepts this binary as a constant component of her identity. To share a hyphenated identity is to forever exist in the in-between, never as one of a “definite whole” (p. 128).

The anthology concludes with a raw and emotionally charged section, Memory/Longing. The authors yearn for the past with such eloquent prose, often desiring the idea of what once was. Farnaz Fatemi spells out this longing in these two sentences taken from “The Color of the Bricks,” a story written like a love letter directed to her parents’ origin cities in Iran. She articulates: “You’ll get to a place you think you know, not the one I know. It’s the tide of your already imagined ideas that I resist” (p. 204). Farnaz clings to her parents’ origin cities in Iran. The land is almost ethereal as it no longer resembles her memories or what her family described in stories passed down through generations. Decades of violence following the Iranian Revolution, alongside a steady military presence, transformed the land into one no longer unrecognizable.

Darius Atefat-Peckham’s “Learning Farsi” illustrates this frustration through the death of his great-grandmother. The two shared a peculiar relationship that paralleled his connection to Iran, identifying a sense of emotional detachment to both. Her death left him longing for a country and culture he previously felt clashed with his American identity. He wished he visited his great-grandmother in Iran—who never ceased to shower him with love during their phone calls—before her passing. His regret and anger shifted to an appreciation for his cultural and ethnic upbringing. The authors in the section reflect on those lost through their short stories, whether it is deceased relatives or war-scarred land.

Published in 2020, “My Shadow Is My Skin” arrives during a critical period. Mahsa Amini’s murder and the protests that followed it prompted precarity in Iranian-American relations. Discourse on Iran mirrors those that infiltrated the media during the Iranian Revolution, at times stating Islamophobic and Orientalist claims that leave Iranians dehumanized. The stories and narratives the authors put forth in the anthology prove significant and relevant as all eyes turn to the resistance, from protests to art exhibits, displayed across Iranian populations. “My Shadow Is My Skin” offers a new glimpse into diasporic writing, leaving the reader wanting to underline and annotate every sentence.

- Copeland is the son of an Iranian mother and American father. He is featured in “My Shadow is My Skin,” and his additional works include “Off the Radar,” “Farewell, Godspeed,” and “A Wonderful Life.”

- Okasi’s works appeared in literary magazines like the “Los Angeles Review of Books” and the “Iowa Review.” He currently teaches creative writing at SUNY Purchase and is working on a novel.

- Darznik’s works include “Song of a Captive Bird,” a Los Angeles Times best seller, and New York Times best seller “The Good Daughter.” She is a professor at California College of the Arts.

- Malek is an assistant professor of international studies at the College of Charleston. Her research interests lie in the intersections of diaspora and transnationalism, citizenship, memory, and cultural production. Her work can be found in sources like “Memory Studies,” “Iran Nameh,” and “Anthropology of the Middle East.”

- Namy is a writer and translator. Her work is featured in “Guernica,” “World Literature Today,” and the “Quaterly Conversation.”

- Fatemi is a poet. Her work is featured in “Grist,” “Catamaran Literary Reader,” and “Tahoma Literary Review” among many others.

- Atefat-Peckham is a poet and essayist. He is a current student at Harvard College, and the Libary of Congress selected him as a National Student Poet, the highest honor offered to youth poets.