Country Overview

Population: 38346720

Population Growth Rate: 2.90%

Religious Groups Breakdown:

Muslim 99%, Other <1%

Youth Unemployment: 16.20%

UNDP HDI: 0.511 (169/189)

Life Expectancy (Male Life Expectancy & Female Life Expectancy): 53.65 (M: 52.1, F: 55.28)

Literacy Rate (Male Literacy Rate & Female Literacy Rate): 37.3 (M: 52.1, F; 22.6)

Primary School Completion Rate: 84.33% (unsure)

Median Age: 19.5

Capital: Kabul

Largest City: Kabul

Nationality: Afghan

Currency: Afghan/AFN

Languages: Afghan Persian/Dari (official, lingua franca) 77%, Pashto (official) 48%, Uzbeki 11%, English 6%, Turkmani 3%, Urdu 3%, Pachaie 1% Nuristani 1%, Arabic 1%, Balochi 1%, Other <1%

Agriculture: Wheat, milk, grapes, vegetables, potatoes, watermelons, melons, rice, onions, apples, gold, grapes, opium, fruits and nuts, insect resins, cotton, handwoven carpets, soapstone, scrap metal

Industries: small-scale production of bricks, textiles, soap, furniture, shoes, fertilizer, apparel, food products, non-alcoholic beverages, mineral water, cement; handwoven carpets; natural gas, coal, copper

Geography

Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked country with Iran to the west, Pakistan to the east and the Hindu Kush mountain range running through its center. It shares a northern border with Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan with one small border touching China. It is the forty-eighth largest country in the world.

Afghanistan’s climate is semi to mostly arid with hot summers and cold winters. The terrain is mostly mountainous, although agriculture is the primary source of income for about 61 percent of the Afghan population (2018 est). Since Afghanistan is on a fault line, it is prone to frequent earthquakes in the Hindu Kush mountains.

Climate Change

Overgrazing, deforestation, soil degradation, desertification, flooding, and pollution are current issues threatening Afghanistan’s environment.

The United Nations Environmental Program (UNDP) estimates that 50% of Afghanistan’s forests have been depleted over the past three decades. Due to illegal logging, wars’ legacy, and scorched earth tactics used by both the Taliban and Soviet Union during the invasion in 1979, the country lost 45.3ha of trees. The illegal timber industry is responsible for the majority of the economy in eastern provinces like Kunar. The Taliban and the Islamic State (IS) have historically exercised most control over the illegal timber industry, utilizing it as a source of funding through taxes on lumber transportation and sales. The illegally-harvested wood is transported through territory and held by insurgent groups and over the border into Pakistan, where it is then sold at high prices.

The consequences of rapid deforestation is felt by the 1.2 million Afghans who have been displaced since 2012 due to the floods and droughts. The lack of government support for reforestation initiatives and reliance on the illegal but lucrative timber trade have triggered these natural disasters. However, in 2020, the government announced plans to plant 13 million trees, specifically pistachio and pine nut trees.The future of this effort was cut short after the Taliban took over in 2021.

Geography Resources

History

Ancient Afghan Civilizations

After more than a dozen excavations conducted in the 1970s in what archeologists called Bactria-Margiana Archeological Complex (BMAC), it was discovered that advanced Aryan tribes had been living in Aryana (ancient Afghanistan) around 2000-1500 BCE. Findings made at BMAC reveal a series of cities and settlements, each with a distinctive and exceptionally large architectural footprint, with temple structure, administrative quarters and defensive walls.

Afghanistan’s climate is semi to mostly arid with hot summers and cold winters. The terrain is mostly mountainous, although agriculture is the primary source of income for about 61 percent of the Afghan population (2018 est). Since Afghanistan is on a fault line, it is prone to frequent earthquakes in the Hindu Kush mountains.

According to legend, large numbers of nomadic migrants traveled south from the Caspian Sea to present-day Afghanistan around this time. They sang hymns passed down through word of mouth from one generation of priests to another. These hymns were added to a collection of volumes known as the Rig Veda that reveal a tribe from centuries earlier, emerging from the Hindu Kush and crossing the Kubha, or Kabul, River around 1500 BCE. Some of the nomadic migrants eventually settled in Afghanistan. In the Avesta, it marks Baktra (present day Balkh), a city in northern Afghanistan, as the birthplace of Zarathustra Spitama (Zoroaster), the founder of Zoroastrianism, one of the first great world religions still practiced today. In 559-330 BCE, the Achaemenid Dynasty built an empire which at its peak spanned three continents, stretching from Libya, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia in the South, to Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) in the west, to the Balkans and Black Sea in the north, and to present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east — making it the largest empire the ancient world had ever seen until 331-330 BCE. Alexander the Great eventually toppled the Persian regime on his eastward march from the Mediterranean through Afghanistan to India.

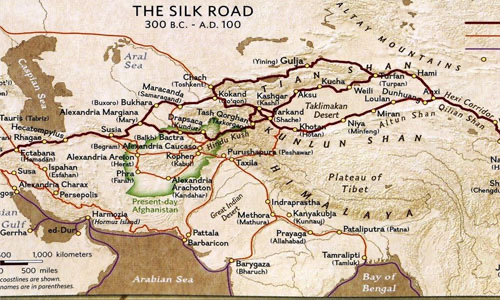

Afghanistan has also been at the center of many ancient civilizations. Its geographical placement between the Chinese, Indian and European civilizations means that through the centuries it has attracted many outsiders, invaders, as well as merchants. Control over Afghanistan has shifted throughout history; Persians, Macedonians, Buddhists, Mongols and Indians have all conquered the area in the past 2,500 years. Beginning in the second century BCE, the Silk Road, passed through central Afghanistan and introduced the exchange of commerce, culture and religion between the major western and eastern civilizations each leaving their marks on the country’s culture.

The Introduction of Islam to Afghanistan

The Islamic conquest of Afghanistan took place between 642 to 1200 CE, beginning with the Umayyad Dynasty’s occupation between the years 708 and 709 CE when it conquered the city of Balkh. By the ninth century, however, the city of Balkh was canonized as the Dome of Islam and its Muslim intellectuals were memorialized as saints. Scholars assert that these large patterns of conversion cannot be explained by violent conversion nor political or economic patronage. Centuries-long process of acculturation and adaptation of rituals and belief systems can be attributed to people living under Muslim rule and the coexistence of multiple religions in the early Islamic period.

The Foundations of Modern Afghanistan

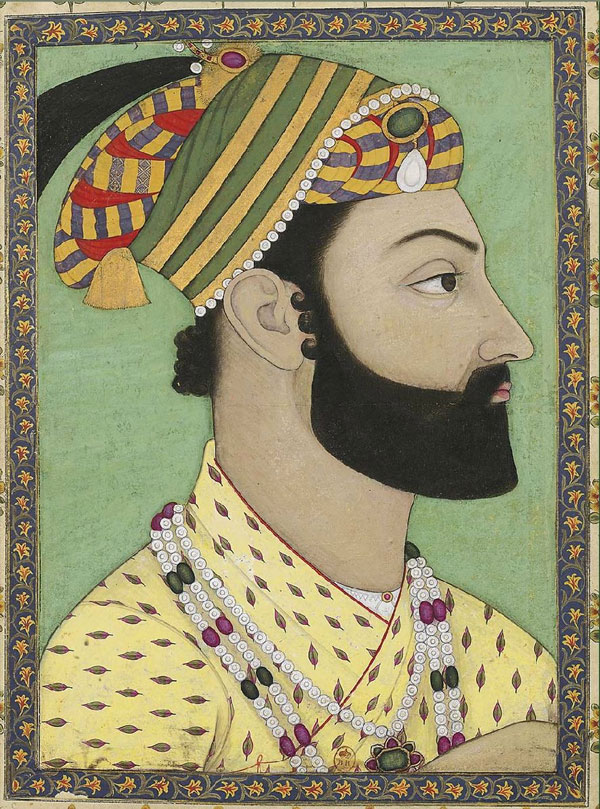

Ahmad Shah Durrani (1747-1772) was one of the first native Afghans to rule the country and is widely considered the founder of modern Afghanistan. By 1761 his Durrani Empire conquered all of the present-day country and parts of Iran, India and Pakistan. After Ahmad Shah’s death the Durrani Empire became plagued with civil war and rebellions, and in 1826 Dost Mohammad Khan established the Barakzai Empire.

The “Great Game” & Afghan Independence

Afghanistan became enmeshed in the “Great Game” during the Barakzai Empire. The “Great Game” was a time when Britain and Russia fought for control over the Middle East. In 1839, Dost Mohammad attempted to form an alliance with Russia after the British turned him away. The British, not wanting Russia to acquire more influence, invaded and conquered Afghanistan marked the first of three Anglo-Afghan Wars. The second war consisted of Britain’s invasion in 1879 in response to Sher Ali Khan's rejection of the British envoy when Russia sent an unwanted diplomatic mission to the country. After the conquest, a British representative was installed in all major cities, granting Britain control of foreign affairs.

The final Anglo-Afghan war took place from May to August in 1919. Amanullah Khan, leader of the Barakzai dynasty, saw a way to free his country from the British Empire. He invaded India, but was repelled. To end this war, the British and Afghans signed the Treaty of Rawalpindi, which set the border between Afghanistan and India, removing British control over Afghanistan. After independence, Amanullah began to westernize his country. He introduced mandatory education, attempted to bar women from wearing the burqa (full-length veil), and changed his title from emir to king. However, conservative Muslim tribes and religious were enraged at these changes causing Amanullah to flee to British-India in 1929.

Afghanistan in the 20th Century

After becoming emir in January of 1929, a leader in the revolt, Habibullah Kalakani was executed in October 1929 as relatives of Amanullah had taken back the country. When Mohammad Nadir Shah, a relative of Amanullah, became king, he used propaganda to ensure Amanullah could never return to Afghanistan. Nadir Shah was assassinated in 1933. His son, Mohammad Zahir Shah, succeeded him at the age of 19. Mohammad established regency, allowing his uncles to manage the country, until he felt he could rule effectively.

In 1963, Zahir Shah took full control of Afghanistan and forced Prime Minister Mohammed Daoud Khan to resign. In 1962, Khan’s goal was to unify the Pashtun people by invading Pakistan in an attempt to form Pashtunistan so that they would be less dispersed. For the next ten years Zahir transformed Afghanistan into a modern democracy by introducing a new constitution that guaranteed free elections, civil rights, and universal suffrage. In 1973, Daoud staged a coup d’état. In lieu of starting a civil war, Zahir resigned and did not return to Afghanistan until 2002.

The Saur Revolution and the 1979 Soviet Invasion

Daoud transformed Afghanistan into a republic and appointed himself president. In 1977, he met with Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Union, after which he motioned to reduce Afghanistan’s relations with the USSR and pivot toward the West. Daoud signed a cooperative military treaty with Egypt, which was allied with the West, and directed the Afghan military and police to begin training with the Egyptian Armed Forces. Just a year after, Daoud was killed during a coup d’état in which the citizens blamed the government for the murder of a prominent member of the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, resulting in the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) taking power.

The coup was a part of the 1978 Saur Revolution. The PDPA announced Daoud had resigned and buried the bodies of him and his family in a mass grave. Various groups of Mujahedeen, Muslim guerilla forces, rose to combat the newly formed pro-Soviet government, citing its secular nature and use of reforms that ran contrary to traditional practices, such as letting women participate in politics. These attacks caused the new government to request help from the USSR and in 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan to support the pro-communist regime.

One of the immediate reactions by foreign states to the Soviet invasion was to fund the Mujahideen. The United States and Saudi Arabia contributed an estimated $40 billion to the rebel groups. It was a costly ten-year war, mainly for civilians in Afghanistan. Between 850,000 and 1.5 million civilians, about 14,500 Soviet troops, and 75-90,000 Mujahideen were killed during Soviet occupation. This war created 5 million refugees and 2 million internally displaced persons (IDPs).

Several factors led to the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989; some of these were heavy economic costs, a high casualty count (about 15,000 Soviet troops), as well as foreign policy change (from Brezhnev to President Mikhail Gorbachev). The government created by the Soviets lasted until 1992. However, the leader was killed by the Taliban in 1996 and the Russian government stopped aiding the regime.

Post-Soviet Afghanistan and the Rise of the Taliban

From 1992-96 Afghanistan was consumed by chaos. There were several factions fighting for power that were supported by governments from different states. For example, Hezb-i Islami was supported by Pakistan until late 1994 while Junbish-i Millil was supported by Uzbekistan until mid-1994. Violence mostly occured in cities, and the countryside was relatively peaceful. In 1996, the Taliban gained power. In the beginning, Afgans welcomed Taliban rule since they succeeded in law and order, but quickly realized the Taliban sought to impose strict religious laws such as requiring women to wear the burqa, banning television, and jailing men whose beards were too short.

The Taliban imposed high taxes due to their monopoly on trade which deteriorated the Afghan economy and infrastructure. The Taliban harboured training grounds for (U.S. designated terrorist group) al-Qaeda, tasked with the training of Taliban military brigades.

Operation Enduring Freedom & War in Afghanistan

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the United States, along with a coalition of countries spanning from Germany to Turkey to Australia, joined forces with the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance with the intention of replacing the Taliban with a new government. This coalition pursued al-Qaeda and Osama bin Laden as a part of a Global War on Terrorism, named Operation Enduring Freedom. The coalition forces are still present in the region although the mission has modified its military operations fromactive measures to prevent opposition from native forces to solely counter-terrorism, focusing on terrorist groups as well as training Afghan security forces, in an effort to make foreign troop withdrawal possible. The number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan peaked in 2010 to 2011 with about 100,000 troops stationed in the region.

While US and NATO forces planned to maintain 13,000 troops in Afghanistan from 2011 to 2016, the US postponed the withdrawal until December 2016 in light of deteriorating security conditions It decided to maintain a force of 8,400 troops in Kabul, Kandahar, Bagram and Jalalabad indefinitely due to Taliban resurgence attempts after the Battle of Kunduz. In early 2017 the number of US troops number was down to 8,400.

Since the withdrawal of U.S. troops began, the U.S. has helped train national troops, and only engage in combat if they are under attack. In June 2017, the Trump Administration announced that 4,000 additional American troops would be deployed to reclaim increasing Taliban territory but no action followed since the president began to question, “Why we've been stuck there for 17 years,” as a result of Afghanistan’s trend toward lawlessness and poor governance.

However, the Trump administration in the U.S. decided to send a significant amount of additional troops to Afghanistan in September 2017. By the end of the year, around 13,000 to 14,000 American troops were positioned in the country as President Trump promised that the US would “win” the war for the American people.

The official U.S. withdrawal process from Afghanistan began in February 2020, when President Trump signed the Doha Agreement with the Taliban, though without participation from the Afghan government. The agreement stipulated that all NATO forces in Afghanistan would withdraw in exchange for: 1) the Taliban preventing al-Qaeda from operating in their territory and 2) a promise of future talks for a ceasefire between the Taliban and the government. As a result of the agreement, the U.S. troop count in Afghanistan dropped with the promise of a full withdrawal by May 2021. However, the last U.S. soldiers left Afghanistan on August 30, 2021.

Between the period of May 1, 2021, and August 15, 2021, the Taliban gained nearly full control of the country. Many top Afghan officials — notably the former President Ashraf Ghani — were forced to abruptly flee in a retreat that incited vast amounts of chaos and uncertainty for the government and Afghan citizens.

History Resources

Government

Structure

The current government of Afghanistan, now known as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is made up of executive bodies headed by the Taliban regime. It operates a shadow government within the administrative government structure already in place. The Taliban head the leadership council, known as the Quetta Shura, and various commissions, which are responsible for key areas such as the economy, education, and health. The leadership council serves as the executive body of the regime and handles the political and military affairs of the government, while the commissions take the place of the ministries that existed under the former government. The interim government announced by the Taliban consists of over thirty appointees, many of whom are either considered terrorists by the United States or are under sanction from the United Nations.

Taliban Leadership

The most senior in leadership is Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada who has been the religious and judicial leader of the Taliban since 2016. As the “Emir of the Faithful,” Akhundzada is allowed to justify the actions of the Taliban’s members as he was a religious scholar, judge, and head of the judiciary.

At the head of the leadership council sits Mullah Muhammad Hassan Akhund as prime minister, one of the founding members of the Taliban.

Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar is another founder of the group that held senior leadership positions during the first Taliban government. He was released from prison as a part of the agreement between the Trump administration and the Taliban in 2018 and served as a senior negotiator in the discussions in Qatar about U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021.

In the role of interior minister, a position of substantial power within the country, is deputy emir Sirajuddin Haqqani. Sirajuddin is the head of the Haqqani network, a terrorist organization with deep ties to Al-Qaeda, and a key military commander of the Taliban. He has been designated a global terrorist by the United States.

Government Resources

International & Regional Issues

Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), and Human Rights

The ongoing wars in Afghanistan have led to the displacement of a large portion of its population. There are estimated to be at least 3.5 million IDPs (est. 2021) within the country, with the majority being women and children. There are also 2.6 million registered Afghan refugees in the world, of whom 2.2 million are registered in Pakistan alone, with many others located in Iran. In light of the events of August 2021, this number has risen and been difficult for the United Nations and human rights watchdogs to estimate. The perennial situation has also created chronic poverty and food insecurity.

Corruption

Police corruption has increased exponentially causing Afghans to face extortion by groups like the Taliban, police, and security forces. Bribes, abuse, and collusion with militants are standard practices in law enforcement. The Taliban continues to exploit the fact that citizens distrust the government to gain support.

Territorial Disputes

To secure its border and control illegal cross-border activities, Pakistan sent troops to various areas in Afghanistan. Disputes surrounding Pakistan’s encroachments on Afghan territory have been dealt with diplomatically. Afghan, Pakistani, and militants from various NATO allies, have clarified borders, and have facilitated discussions since 2014 to collaborate on counterterrorism efforts against the Taliban. In June 2017, military officials in Pakistan announced that they will proceed with building a fence and heighten security measures along the 1,500 mile border with Afghanistan. As of August 3, 2021, the fence is 90% complete, with plans to finish the project by the end of the year.

The poppy trade is cause for concern for many surrounding countries, not least Russia and former Soviet states such as Uzbekistan. The opiates which stem from the poppy are smuggled from Afghanistan through Central Asia before ending up in Russia (more in the Economy section).

COVID-19

The first case of Covid-19 was recorded in Afghanistan on July 3, 2020, and by July 6, 2022, there were 182,873 confirmed cases with 7,725 reported deaths. As of late June 2022, a total of 6,445,359 vaccine doses were administered. Covid exacerbated poverty and food insecurity rates.

International & Regional Issues Resources

Economy

The gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 was $20.12 billion USD, which placed Afghanistan’s economy as the 113th lowest in the world. In December of 2021, many predicted a decline of GDP by $16 billion USD. Already the poorest country in Asia, Afghanistan’s economic base is too small to support its population, with annual per capita income having declined by $150 USD in just two years. The pullout of foreign aid by Western governments painted a bleak picture for the future of Afghanistan's econonomy. In fact, around 75% of the government’s budget was previously funded by foreign grants. Historically, the majority of the Taliban’s funding comes from illegal activities, such as extortion, kidnapping, and drug trafficking, particularly in opium.

According to the World Bank, 37% cannot afford food and another 33% can only afford food. In April 2022, 87% of Afghans reported that it was “difficult” or “very difficult” to live off their household income. In 2020, 49.4% of the population lived below the national poverty line. Afghanistan is rich in natural resources such as gas and coal, however, these industries are untapped due to poor technology forcing the economy to rely on agriculture.

Despite corruption in Afghanistan, the country has made strides to improve its infrastructure. As of 2020, over 97.7% of Afghans had access to electricity and over 67% had access to clean water, a big milestone. Opium poppy plant production is significant to Afghanistan because of its high value, though it is illegal to farm. Opium, derived from the poppy seed bulb, is used in several drugs, including heroin, morphine, and codeine that are illegal in many countries due to their addictive properties. For years, the Taliban taxed poppy production in areas it controlled, serving as a major source of income. In 2022, the Taliban renewed its stance on poppy production even though it was banned in 2000. Since then, the trade has grown exponentially. According to a report by the UNODC, Afghan opium and heroin made up 80% of the worldwide market, deflecting U.S. efforts to curb the production and flow of drugs.

The UN estimates that the Taliban made more than $400 million from the drug trade between 2018 and 2019, with one report from the U.S. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan estimating that the narcotics trade accounts for up to 60% of their annual revenue.

Society

Afghanistan is one of the most under developed countries worldwide, according to the 2020 UN Human Development Index (HDI) Report. The HDI of a nation is calculated based on education, life expectancy, and gender equality. The country ranked 1 has the highest human development while 179th represents the lowest score.

Afghanistan had a population of 38,346,720 (2022). Most of the population is involved in farming, herding, or both. In 2021, the median age in Afghanistan is 19.5 years old, largely due to the steep population increase and a relatively low life expectancy.

NPR noted: “One of the most dramatic changes in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban is the increase in average life expectancy from 45 to 62 years. That gain is almost entirely a function of reductions in child mortality due to the spread of basic health services.”

There are several Afghan ethnic groups. The Pashtun people make up 42% of the population and are often referred to as “true Afghans,” with roots spanning the last 300 years. There are 60 different Pashtun tribes. They are recognizable by the Pashto language their Pashtunwali lifestyle — a set of moral guidelines each tribe follows.

The Tajiks comprise more than a quarter of the population (27%). Tajiks are instead identified by the region they reside in. Tajiks are mainly goat herders and mountain farmers. In addition, there are several small minorities such as the Uzbeks (9%) who primarily reside in the northern regions of Afghanistan and are typically bilingual, speaking Farsi (Afghan Persian) and Uzbek. The Hazaras (9%) live in the mountains of central Afghanistan and have Mongolian ancestry. The Aimak (4%) are Persian-speaking nomads who dwell in western Afghanistan and are largely Sunni. Turkmen (3%) are a nomadic people who are traditionally yak herders. The Balochi (2%) live in the deserts of the Helmand province in Afghanistan. They are known to speak other ethnic Afghan languages including Balochi, Dari and Pashto.

Conflict, extreme poverty, lack of adequate medical facilities for children and new mothers contribute to Afghanistan’s high infant mortality rate. However, some modest improvements have been made. UNICEF, USAID, Save the Children, and others, have taught midwives and community health workers how to work in remote areas in hopes of reducing infant mortality rates. Agencies also invested in and provided basic health care, nutrition, clean water and sanitation to improve the health of mothers and their newborns through new clinics. Despite these strides, Afganistan has the highest infant mortality rate in the world. The average life expectancy in 2022 was 53.65, a decline since the Taliban takeover.

Afghanistan also has one of the lower literacy rates at 37.3% percent (2021) and is expected to decline because of the Taliban’s ban on girls attending school. Among males, 52.1% are literate, while 22.6% of the female population is literate. Men typically attend school for 13 years, 5 more years than women. As of 2020, 67% of school-age boys and 48% of school-age girls are enrolled in school. An even smaller percentage attend secondary school . Since the cultural norm in Afghanistan is to have gender-segregated schools, there are not enough women to teach school girls which is why there is a stark contrast between men and women for educational opportunities. One way the international community has helped close this large gap in gender education is through the UN’s Afghanistan Girls’ Education Initiative (AGEI), a program whose key objectives are to strengthen national and international commitment for girls’ education. AGEI works with the Ministry of Education and provides incentives like teacher preparation classes, scholarships for teachers to further their education, and increase community support for female teachers. AGEI tackles the crux of the issues by encouraging women to become teachers because many parents do not allow their girls to be taught by male teachers past grade four.

In search of a better chance of survival, Afghans either found safety in rural areas or have fled to Pakistan and Iran. The U.S. withdrawl added 660,000 more people to the three million already displaced. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is currently working on reintegrating internally displaced persons (IDPs) into Afghan society by offering cash grants to returning families, providing counsel in health, legal and social issues, and increasing participation in the program through information sharing with Afghanistan government agencies.

Society Resources

LGBTQ+ Issues

The law in Afghanistan currently criminalizes consensual same-sex relations. Under sharia law, conviction of same-sex sexual conduct is punishable by death, flogging, or imprisonment. Sex between men is a criminal offense punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment and sex between women with up to one year of imprisonment. Individual Taliban members have made public statements confirming that their interpretation of sharia allows for the death penalty for homosexuality.

Due to the criminalization of sexuality, members of the LGBT+ community cannot access certain health services and lack legal protection in the workforce. Since the 2021 Taliban takeover, members of the community have reported being physically and sexually assaulted. Furthermore, there are also reports of families purposely outing LGBT+ members in order to curry favor with the Taliban.

LGBTQ+ Resources

Religion

Almost all Afghans are Muslims (99.74%). Sunni Islam has an 89.01% majority, Shia Islam makes up 10.72% of the population and less than 1% is Sufi.

Afghan religious traditions are a combination of traditional Islam, Sufism, and religious folk traditions, known as “folk Islam.” Generally, tribal traditions are more important to Afghans than the scholarly study of Islam.

There are two types of Muslim religious leaders, mullah imams and ulama. The mullah imam usually are not formally educated and interpret and extend the religion as it applies to daily life. The ulama, however, are trained religious scholars who interpret and uphold Islamic (Sharia) law and scriptural traditions of the Quran in the Fiqh School of jurisprudence. The school deals with the observance of rituals, morals and social legislation. When the Taliban came to power they imposed their own interpretation of religious laws on the Afghan people. The Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice enforced prohibitions on behavior the Taliban deemed un-Islamic like requiring women to wear the head-to-toe burqa, or chadri.

Religion Resources

Culture

General

Afghanistan’s cultural heritage is multifaceted due to the many ethnic tribes and shifts in various empires that have occupied the area. From its critical position on the ancient Silk Road that stretches from Europe to China, Afghanistan absorbed traditions from India, Persia, and Central Asia and blended them into a distinct artistic culture.

Afghanistan has endured a history of violence that has shaped, and at times hindered, cultural development. Decades of civil unrest that began in the 1970s threatened the heritage. The most recent example of this was the strict laws on music, entertainment, and literature imposed by the Taliban rule in the late 1990s. As a result, Afghanistan’s artisans were forced to leave their country or abandon their craft. The old city of Kabul, once a bustling center of craft and commerce, turned mundane and bleak.

Art

Afghanistan shares a history of miniature paintings with Iran, as the Persian Empire once included Afghanistan within its borders. Miniature painting is done on paper generally presented within a book. This granted more freedom for its artists because they could choose their readers if they wanted to express certain opinions.

In conjunction with the rise of miniature painting, the practice of illumination flourished in Afghanistan. Since the miniature painting takes up part of a page, it is bordered with gold leaf or silver gild. The border is considered equally important to the painting, and is illustrated abstractly, similar to Islamic geometric art one might see in mosques.

Chinese influences are prevalent in these paintings as evidenced by depictions of natural scenes in a traditionally Chinese style. Some miniature paintings feature Buddhist imagery before Afghanistan’s widespread adoption of Islam. Perhaps the most famous of the miniature painters is Kamal Ud-Din Behzad. Behzad emphasized inorganic structures and architecture in his paintings, using their presence to frame the scene in which his characters would interact. He also would position his characters expertly in order to illustrate a clear narrative. Typical to miniature painting were his use of bright and vibrant colors contrasted with relatively neutral backgrounds. Check out one of his paintings here.

Oral poetry was another form of expression used in Afghanistan that draw on themes of grief, war, love, and politics. The most notable form of Afghan poetry is called the landay, meaning “short, poisonous snake” in Pashto. The two-line form that were exchanged through word of mouth came from Iran thousands of years ago and is known for its short length, rigid form, and biting sarcasm. This poetic tradition is widely practiced in Afghanistan today.

Though traditionally exchanged between men, women have used landays as a form of solidarity and resistance against the highly patriarchal Afghan culture. Authors are shielded from the social consequences of its content because it was hard to track them down because they were not in writting. Some examples of Afghan landay are below:

“Listen, friends, and share my despair.

My cruel father is selling me to an old goat with white hair.”

The first poem, for example, protests the forced marriage of a daughter to an older man. Similar to the example, landays often draw on the themes of grief, war, love, politics, nationalism, and love.

Afghanistan is known for its unique rugs. Although many weavers fled to Pakistan in 1979, during the civil war, and the Taliban rule, the revival of carpet weaving is awakening as more artists return home. Traditional rugs are made of wool and contain two primary colors: bright red and dark blue. The traditional gül pattern (a repeated octagonal figure) is a prominent motif. The creations of Baluchi War Rugs are a contemporary take on the traditional art form and depict scenes of warfare (i.e. helicopters, machine guns, and missiles) in their designs.

War and Beyond

The legacy of n from the Taliban and Soviet invasion is displayed in National Museum of Afghanistan, also known as the Kabul Museum. The museum, established in 1922, was renowned for holding the largest collection of art, artifacts and other treasures of ancient Central Asia, Rome, Greece, Egypt, and other parts of Asia. The Taliban bombed the museum in 1993, destroying some of the precious artifacts. Attempts to preserve the museum’s relics by the United Nations did not suffice as robbers got there faster. Despite the Taliban’s success, the museum is slowly rebuilding. Collections of art, hidden away during the turmoil, are being gathered and brought back to the museum.

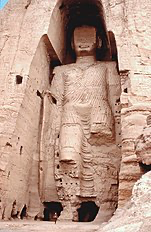

The Taliban went on to destroy the world’s largest Buddha statues dating back to the 5th century because they were deemed as un-Islamic Like the museum, the United Nations Educational and Scientific Cultural Organization and International Council on Monuments and Sites are working to reassemble the broken pieces of the ancient statues with the help of modern materials. The British non-governmental organization Turquoise Mountain, has transformed the Murad Khani district of Old Kabul from slum conditions into a vibrant cultural and economic center by renovating the historic buildings and opening a primary school and a medical clinic. It founded Afghanistan’s premier institution for vocational training in the arts. Dedicated to teaching a new generation of Afghan artisans in woodwork, calligraphy, ceramics, jewelry design, and other crafts, Turquoise Mountain is reviving the nation’s proud cultural legacy. Afghan woodworkers created magnificent wood arcades, screens, and a pavilion, all carved by hand from Himalayan cedar are displayed in the Smithsonian Museums of Asian Art in Washington, DC.

Another arts initiative, the Center for Contemporary Art Afghanistan, is a small arts center in Kabul. It offers courses, workshops and a studio space for young artists, mainly women between the ages of 16 and 25. There are still only two art colleges in Afghanistan, the Faculties of Fine Arts in Kabul and Herat Universities.

Graffiti as its medium has gained popularity in the capital city. A collective, Berang, features a young female artist who reproduces the shapeless figure of the blue burqa-clad woman in unexpected ways. Using public spaces in Kabul to spread messages on conflict and social issues countered the repressive Taliban rule. Shamsia Hassani works to establish annual graffiti workshops across the country to change the way society views women.

Food

Drawing on its diverse population, and its extraordinary geographic position, Afghans created a distinctive culinary tradition composing of wheat, corn, barley, and rice. The cuisine heavily features dairy in its recipes. Kabuli Palaw is the national dish of Afghanistan. It consists of rice, carrots, lamb, and raisins. The long-grain rice is boiled in a rich sauce to absorb its flavor, then topped with fried carrots, raisins, orange peels, and chopped nuts. The meat is then buried in the rice and baked. The hearty dish is common throughout the Middle East is adapted to suit local tastes, such as roz bukhari in Saudi Arabia.

A staple of the Afghan diet is naan, a long and thin oval shape similar to pita bread. Naan can be found all across West, Central, and South Asia; you might recognize it from Indian cuisine. There are three other main types of Afghan bread: Lavash, which is often used as a plateas plate for stews, Obi Non, a thicker version of Naan, and Chapati, which is a type of round, thin bread. These types of bread are typically used in place of cutlery to scoop or grab food during a meal.

Food Resources

Literature & Film

In 2003, Afghan-born American novelist Khaled Hosseini introduced the world to Afghanistan through his New York Times best-selling novel The Kite Runner, capturing the tradition of kite racing in the book and life during the fall of Afghanistan’s monarchy, the Soviet invasion, and rise of the Taliban. Khaled Hosseini is one of Afghanistan’s most successful authors.

Cinema, as well as television, was banned under the Taliban. Currently the development of Afghan movies and television is in the infancy stage, but growing quickly. The Afghan Star, a popular television show, is an Afghan version of American Idol. However, this industry is met with challenges because of the lack of necessary infrastructure resistance.

Literature & Film Resources

Clothing

Often colorful and hand-woven, Afghan clothing is traditionally intricate – the more detail, the higher the price. Gold threads and beads are sometimes sewn into the highest quality clothing, though this is generally reserved for weddings or other special occasions. Clothing for both sexes is typically baggy and loose, a pragmatic design meant to relieve the exceptional heat in Afghanistan and adhere to Islamic standards of modesty.

Women’s clothing is usually stitched with light linen in complex geometric shapes One of the most common styles of women’s dress is called the Firaq partug which is composed of three separate articles. The Chador is a head scarf that covers the hair and extends down to the woman’s torso. This is often richly colored and patterned. The second component, the Firaq, is a garment resembling a dress, though the length of the dress can vary (sometimes ending at the knee, and other times at the ankles). The third component, the Partug, is a baggy garment tied around the waist that extends to the ankles. The Partug is quite similar to other types of South Asian baggy pants, collectively called the Shalwar. The Burqa is a full-body covering with a small mesh-window that enables sight. It was mandatory for women to wear a Burqa under Taliban rule, but its presence in the country predates their reign. The Burqa continues to be worn as a cultural and traditional vestige. Men’s clothing did not have bright and complex colors although today it has become fashionable to wear brighter colors and geometric patterns for men. A typical Afghan outfit is called the Perahan tunban. The two words refer to the top and bottom garment. The Perahan is wide and long so the material hangs away from the body. Depending on the region, the Perahan can end anywhere from the knees to the feet. The tunban is similarly loose, using a lot of cloth (sometimes several yards worth!) so that it bunches up at the lower leg. Any excess cloth is looped around the waist.

Men’s headwear is varied, generally reflecting their ethnic identity and status in Afghan society. One example of prominent headwear is the karakul, which derives its name from the sheep whose wool the hat is made out of. The triangular, conical hat is worn across Afghanistan, and has been for generations. The pakol is a hat that is said to resemble a pita bread when worn, as the top is rounded and the sides roll up to form what takes a similar shape to a pita bread.

Clothing Resources

Music

Indian, Persian, Arabic, and Mongol styles have all had a part in the creation of Afghan music. Since the fall of the Taliban, traditional Afghan has had a rebirth. Klasik (classical Afghan music), Afghan pop and Pashto have all grown in popularity. Some sub-genres of Pashto music include Pashto poetry and traditional folk music which are performed for weddings or funerals. One popular traditional Pashto group is the Kabul Ensemble.

Music Resources

Sites & Places of Interest

Many architectural treasures have been reduced to rubble. The ruins, from the famed Bamiyan Buddhas to royal palaces, hold much educational value despite their poor condition. In fact, present-day Kabul is a living microcosm of the country’s still tumultuous narrative. Reconstruction efforts and renewed interest in traditional cultural practices may help preserve at-risk structures. One can also still find vast evidence of former occupiers throughout the country such as the shells of military vehicles and foreign styles of architecture.

The most famous site is the Shrine of the Sacred Cloak of the Prophet Muhammad in Kandahar. This ornate and beautifully decorated shrine, adjacent to the local mosque, is the home of what is believed to be the cloak worn by the Islamic Prophet Muhammad — the most sacred religious relic in Afghanistan.

The legend of how the cloak came to Kandahar is a popular tale. During his reign in the late 1700s, King Ahmad Shah Durrani traveled to the city of Bokhara, once a major center for Islamic culture, now a modern city in Uzbekistan. There, he asked to “borrow” the cloak of the Prophet Muhammad from its caretakers and bring it back to Kandahar. Suspicious of the King’s intentions, the caretakers forbid him to leave the city of Bokhara with the cloak. To reassure them, the king pointed to a stone in the ground and made a promise. He said, “I will never take the cloak far away from this stone.” Sufficiently at ease, the caretakers lent the cloak. King Ahmed kept his promise. He had the stone removed from the ground and taken to Kandahar along with the cloak, both of which have remained there since.

The cloak’s religious significance is a great symbol of power. It is only shown to leaders of Afghanistan and occasionally brought out to calm the public in times of crisis. The last time the cloak was seen in public was in 1996 when Taliban leader Mohammad Omar visited the shrine after gaining control of Kandahar.

Located outside the capital city of Kabul, another famous historical site is the ancient fortress of Bala Hissar. The fortress was built in the 5th century CE would become historical focal point in many of Afghanistan’s major wars due to its strategic positioning at the end of the Kuh-e-Sherdarwaza Mountain, overlooking the southern end of Kabul. During the Anglo-Afghan Wars, the fortress suffered major damages and was rebuilt in the early 1880s. The Bala Hissar took place at the fortress during the Soviet Afghan War in 1979. Members of the Afghanistan Liberation Organization (opponents of Afghanistan’s pro-Russian regime) staged riots to overthrow the government. In the 1990s, it was the place of many battles fought between warring factions vying for power during the Afghan Civil War and today, is currently controlled by Afghan military forces.

Other places of interest include the Band-e-Amir National Park, named the country’s first in 2009; the beautiful Blue Mosque (also referred to as the Shrine of Ali) of Mazar-e-Sharif; and the stunning Panjshir Mountains, located north of Kabul.

Sites & Places of Interest Resources

Sports

Taliban suppression of cultural freedom also applied to sports. The popular national sport, Buzkashi (buz-cash-e: translated as goat-grabbing), was also restricted during Taliban rule. Buzkashi is similar to polo in that it is played on horseback, but the objective of the game is to move a headless goat carcass to the goal. A single game can last for days.

Football (U.S. soccer) and cricket are also popular sports. Cricket gained popularity in the 1990s among Afghan refugees in Pakistan. When these refugees returned home in 2001, they brought their passion for cricket back to Afghanistan. That same year, Afghanistan’s cricket team became an affiliate member of the International Cricket Council (ICC). The Afghanistan cricket team reached success by winning the ACC Twenty20 Cup (in 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013) and the team was the 2010 Asian Games Silver Medalist and winners of the 2012 Asia vs. Caribbean Twenty20 Championships.

The Afghanistan national football team was founded in 1922 and has been affiliated with FIFA since 1948. The 1948 Summer Olympics is the only time Afghanistan’s team has made an Olympic appearance. From 1984-2002, the Soviet Invasion of 1979 interrupted international matches in Afghanistan. In 2003, Afghanistan’s national football team embarked upon their first ever FIFA qualifying campaign which ended in two losses to Turkmenistan and an unsuccessful bid for the 2008 FIFA World Cup. Afghanistan’s National Football Team achieved its highest FIFA world ranking in April 2013 climbing to 139th overall. As of October 26, 2021, they are ranked 152nd in the FIFA world rankings.

A favorite pastime of Afghan boys was kite flying before the Taliban banned it. Capturing this tradition in his novel The Kite Runner (2003), Khaled Hosseini writes of his life in Afghanistan during the fall of Afghanistan’s monarchy, the Soviet invasion and rise of the Taliban. His fondest and most tragic memories revolve around kite fighting, an event that included the entire community. Hosseini is one of Afghanistan’s most successful authors.

Women became more involved in sports after the official fall of the Taliban in 2001, but continued to face opposition from social conservative elements in society who felt such activity was un-Islamic. Other challenges female athletes faced were lack of financial support and experienced coaches. Efforts to establish women’s soccer and cycling teams saw minimal success, though Afghan women have medaled in taekwondo. Kamia Yousufi is an Afghan sprinter who as Afghanistan’s sole female athlete at the Rio de Janeiro Olympics in 2016. She finished in 22nd place in the preliminary round, setting a new national record for Afghanistan. The new Taliban regime has banned women’s sports where their bodies might be seen, such as cricket. In September 2021, over 100 people associated with the Afghanistan women’s soccer team fled to Pakistan to escape potential threats from the Taliban.

Sports Resources

Latest News & Commentary on Afghanistan

Additional Resources