The Middle East Research and Information Project provides a detailed chronicle of the unrest between the Arabs and the Israelis, tracing this conflict over land and recognition to its origins in the late nineteenth century. This primer looks at the core developments and issues that have led to the current impasse, equipping the reader with context and background to understand the conflict and inform others. Here we include the introduction as well as the sections on the Land and the People, the British Mandate in Palestine, and the UN Partition Plan. Click here for a printable .PDF of the complete report.

Introduction

The conflict between Palestinian Arabs and Zionist (now Israeli) Jews is a modern phenomenon, dating to the end of the nineteenth century. Although the two groups have different religions (Palestinians include Muslims, Christians and Druze), religious differences are not the cause of the strife. The conflict began as a struggle over land. From the end of World War I until 1948, the area that both groups claimed was known internationally as Palestine. That same name was also used to designate a less well-defined “Holy Land” by the three monotheistic religions. Following the war of 1948–1949, this land was divided into three parts: the State of Israel, the West Bank (of the Jordan River) and the Gaza Strip.

It is a small area—approximately 10,000 square miles, or about the size of the state of Maryland. The competing claims to the territory are not reconcilable if one group exercises exclusive political control over all of it. Jewish claims to this land are based on the biblical promise to Abraham and his descendants, on the fact that the land was the historical site of the ancient Jewish kingdoms of Israel and Judea, and on Jews’ need for a haven from European anti-Semitism. Palestinian Arab claims to the land are based on their continuous residence in the country for hundreds of years and the fact that they represented the demographic majority until 1948. They reject the notion that a biblical-era kingdom constitutes the basis for a valid modern claim. If Arabs engage the biblical argument at all, they maintain that since Abraham’s son Ishmael is the forefather of the Arabs, then God’s promise of the land to the children of Abraham includes Arabs as well. They do not believe that they should forfeit their land to compensate Jews for Europe’s crimes against Jews.

The Land and the People

In the nineteenth century, following a trend that emerged earlier in Europe, people around the world began to identify themselves as nations and to demand national rights, foremost the right to self-rule in a state of their own (self-determination and sovereignty). Jews and Palestinians both started to develop a national consciousness and mobilized to achieve national goals. Because Jews were spread across the world (in diaspora), the Jewish national movement, or Zionist trend, sought to identify a place where Jews could come together through the process of immigration and settlement. Palestine seemed the logical and optimal place because it was the site of Jewish origin. The Zionist movement began in 1882 with the first wave of European Jewish immigration to Palestine.

At that time, the land of Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. This area did not constitute a single political unit, however. The northern districts of Acre and Nablus were part of the province of Beirut. The district of Jerusalem was under the direct authority of the Ottoman capital of Istanbul because of the international significance of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem as religious centers for Muslims, Christians and Jews. According to Ottoman records, in 1878 there were 462,465 subject inhabitants of the Jerusalem, Nablus and Acre districts: 403,795 Muslims (including Druze), 43,659 Christians and 15,011 Jews. In addition, there were perhaps 10,000 Jews with foreign citizenship (recent immigrants to the country) and several thousand Muslim Arab nomads (Bedouin) who were not counted as Ottoman subjects. The great majority of the Arabs (Muslims and Christians) lived in several hundred rural villages. Jaffa and Nablus were the largest and economically most important towns with majority-Arab populations.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, most Jews living in Palestine were concentrated in four cities with religious significance: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias. Most of them observed traditional, orthodox religious practices. Many spent their time studying religious texts and depended on the charity of world Jewry for survival. Their attachment to the land was religious rather than national, and they were not involved in—or supportive of—the Zionist movement that began in Europe and was brought to Palestine by immigrants. Most of the Jews who emigrated from Europe lived a more secular lifestyle and were committed to the goals of creating a modern Jewish nation and building an independent Jewish state. By the outbreak of World War I (1914), the population of Jews in Palestine had risen to about 60,000, about 36,000 of whom were recent settlers. The Arab population in 1914 was 683,000.

The British Mandate in Palestine

By the early years of the twentieth century, Palestine had become a trouble spot of competing territorial claims and political interests. The Ottoman Empire was weakening, and European powers were strengthening their grip on areas along the eastern Mediterranean, including Palestine. During 1915–1916, as World War I was underway, the British high commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon, secretly corresponded with Husayn ibn ‘Ali, the patriarch of the Hashemite family and Ottoman governor of Mecca and Medina. McMahon convinced Husayn to lead an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which was aligned with Germany against Britain and France in the war. McMahon promised that if the Arabs supported Britain in the war, the British government would support the establishment of an independent Arab state under Hashemite rule in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, including Palestine. The Arab revolt, led by Husayn’s son Faysal and T. E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), was successful in defeating the Ottomans, and Britain took control over much of this area during World War I.

But Britain made other promises during the war that conflicted with the Husayn-McMahon understandings. In 1917, the British foreign minister, Lord Arthur Balfour, issued a declaration (the Balfour Declaration) announcing his government’s support for the establishment of “a Jewish national home in Palestine.” A third promise, in the form of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, was a secret deal between Britain and France to carve up the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire and divide control of the region.

After the war, Britain and France convinced the new League of Nations (precursor to the United Nations), in which they were the dominant powers, to grant them quasi-colonial authority over former Ottoman territories. The British and French regimes were known as mandates. France obtained a mandate over Syria, carving out Lebanon as a separate state with a (slight) Christian majority. Britain obtained a mandate over Iraq, as well as the area that now comprises Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and Jordan.

In 1921, the British divided this latter region in two: East of the Jordan River became the Emirate of Transjordan, to be ruled by Faysal’s brother ‘Abdallah, and west of the Jordan River became the Palestine Mandate. It was the first time in modern history that Palestine became a unified political entity.

Throughout the region, Arabs were angered by Britain’s failure to fulfill its promise to create an independent Arab state, and many opposed British and French control as a violation of Arabs’ right to self-determination. In Palestine, the situation was more complicated because of the British promise to support the creation of a Jewish national home. The rising tide of European Jewish immigration, land purchases and settlement in Palestine generated increasing resistance by Palestinian peasants, journalists and political figures. They feared that the influx of Jews would lead eventually to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. Palestinian Arabs opposed the British Mandate because it thwarted their aspirations for self-rule, and they opposed massive Jewish immigration because it threatened their position in the country.

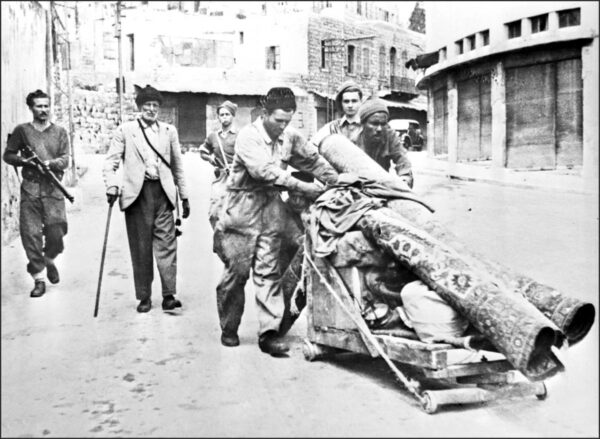

In 1920 and 1921, clashes broke out between Arabs and Jews in which roughly equal numbers from both communities were killed. In the 1920s, when the Jewish National Fund purchased large tracts of land from absentee Arab landowners, the Arabs living in these areas were evicted. These displacements led to increasing tensions and violent confrontations between Jewish settlers and Arab peasant tenants.

In 1928, Muslims and Jews in Jerusalem began to clash over their respective communal religious rights at the Western (or Wailing) Wall. The Wall, the sole remnant of the second Jewish Temple, is the holiest site in the Jewish religious tradition. Above the Wall is a large plaza known as the Temple Mount, the location of the two ancient Israelite temples (though no archaeological evidence has been found for the First Temple). The place is also sacred to Muslims, who call it the Noble Sanctuary. It now hosts the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, believed to mark the spot from which the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven on a winged horse, al-Buraq, that he tethered to the Western Wall, which bears the horse’s name in the Muslim tradition.

On August 15, 1929, members of the Betar Jewish youth movement (a pre-state organization of the Revisionist Zionists) demonstrated and raised a Zionist flag over the Western Wall. Fearing that the Noble Sanctuary was in danger, Arabs responded by attacking Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed. Among the dead were 64 Jews in Hebron. Their Muslim neighbors saved many others. The Jewish community of Hebron ceased to exist when its surviving members left for Jerusalem. During a week of communal violence, 133 Jews and 115 Arabs were killed and many wounded.

European Jewish immigration to Palestine increased dramatically after Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933, leading to new land purchases and Jewish settlements. Palestinian resistance to British control and Zionist settlement climaxed with the Arab revolt of 1936–1939, which Britain suppressed with the help of Zionist militias and the complicity of neighboring Arab regimes. After crushing the Arab revolt, the British reconsidered their governing policies in an effort to maintain order in an increasingly tense environment. They issued the 1939 White Paper (a statement of government policy) limiting future Jewish immigration and land purchases and promising independence in ten years, which would have resulted in a majority-Arab Palestinian state. The Zionists regarded the White Paper as a betrayal of the Balfour Declaration and a particularly egregious act in light of the desperate situation of the Jews in Europe, who were facing extermination. The 1939 White Paper marked the end of the British-Zionist alliance. At the same time, the defeat of the Arab revolt and the exile of the Palestinian political leadership meant that the Palestinians were politically disorganized during the crucial decade in which the future of Palestine was decided.

The United Nations Partition Plan

Following World War II, hostilities escalated between Arabs and Jews over the fate of Palestine and between the Zionist militias and the British army. Britain decided to relinquish its mandate over Palestine and requested that the recently established United Nations determine the future of the country. But the British government’s hope was that the UN would be unable to arrive at a workable solution, and would turn Palestine back to them as a UN trusteeship. A UN-appointed committee of representatives from various countries went to Palestine to investigate the situation. Although members of this committee disagreed on the form that a political resolution should take, the majority concluded that the country should be divided (partitioned) in order to satisfy the needs and demands of both Jews and Palestinian Arabs. At the end of 1946, 1,269,000 Arabs and 608,000 Jews resided within the borders of Mandate Palestine. Jews had acquired by purchase about 7 percent of the total land area of Palestine, amounting to about 20 percent of the arable land.

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to partition Palestine into two states, one Jewish and the other Arab. The UN partition plan divided the country so that each state would have a majority of its own population, although a few Jewish settlements would fall within the proposed Arab state while hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs would become part of the proposed Jewish state. The territory designated for the Jewish state would be slightly larger than the Arab state (56 percent and 43 percent of Palestine, respectively, excluding Jerusalem), on the assumption that increasing numbers of Jews would immigrate there. According to the UN partition plan, the area of Jerusalem and Bethlehem was to become an international zone.

Publicly, the Zionist leadership accepted the UN partition plan, although they hoped somehow to expand the borders assigned to the Jewish state. The Palestinian Arabs and the surrounding Arab states rejected the UN plan and regarded the General Assembly vote as an international betrayal. Some argued that the UN plan allotted too much territory to the Jews. Most Arabs regarded the proposed Jewish state as a settler colony and argued that it was only because the British had permitted extensive Zionist settlement in Palestine against the wishes of the Arab majority that the question of Jewish statehood was on the international agenda at all.

Fighting began between the Arab and Jewish residents of Palestine days after the adoption of the UN partition plan. The Arab military forces were poorly organized, trained and armed. In contrast, Zionist military forces, although numerically smaller, were well organized, trained and armed. By early April 1948, the Zionist forces had secured control over most of the territory allotted to the Jewish state in the UN plan and begun to go on the offensive, conquering territory beyond the partition borders, in several sectors.

On May 15, 1948, the British evacuated Palestine, and Zionist leaders proclaimed the State of Israel. Neighboring Arab states (Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Iraq) then invaded Israel, claiming that they sought to “save” Palestine from the Zionists. Lebanon declared war but did not invade. In fact, the Arab rulers had territorial designs on Palestine and were no more anxious than the Zionists to see a Palestinian state emerge. During May and June 1948, when the fighting was most intense, the outcome of this first Arab-Israeli war was in doubt. But after arms shipments from Czechoslovakia reached Israel, its armed forces established superiority and conquered additional territories beyond the borders the UN partition plan had drawn up for the Jewish state.

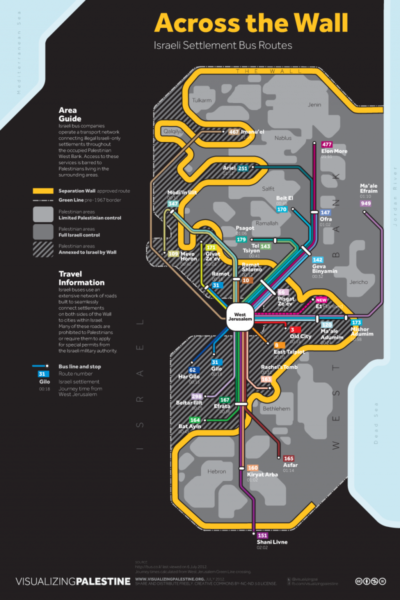

In 1949, the war between Israel and the Arab states ended with the signing of armistice agreements. The country once known as Palestine was now divided into three parts, each under a different political regime. The boundaries between them were the 1949 armistice lines (the “Green Line”). The State of Israel encompassed over 77 percent of the territory. Jordan occupied East Jerusalem and the hill country of central Palestine (the West Bank). Egypt took control of the coastal plain around the city of Gaza (the Gaza Strip). The Palestinian Arab state envisioned by the UN partition plan was never established.

Click here for a printable .PDF of the complete report which includes additional sections on the Palestinian Refugees, Palestinian Citizens of Israel, the June 1967 War, UN Security Council Resolution 242, the Palestine Liberation Organization, the First Intifada, the Oslo Accords, the 2002 Arab Peace Plan, the Separation Barrier, the Road Map and the Quartet, Israel’s Withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, the 2006 Palestinian Elections and the Rise of Hamas, Israel’s Siege of the Gaza Strip, Palestinian Statehood and the UN, and more.